Sins, and Horror

So you may have noticed — I certainly have — that I’ve generally use Fantasy and Horror games for examples in this treatise. Of course there are more genres and styles than those two, but it does bring up a fascinating dichotomy in the hobby.

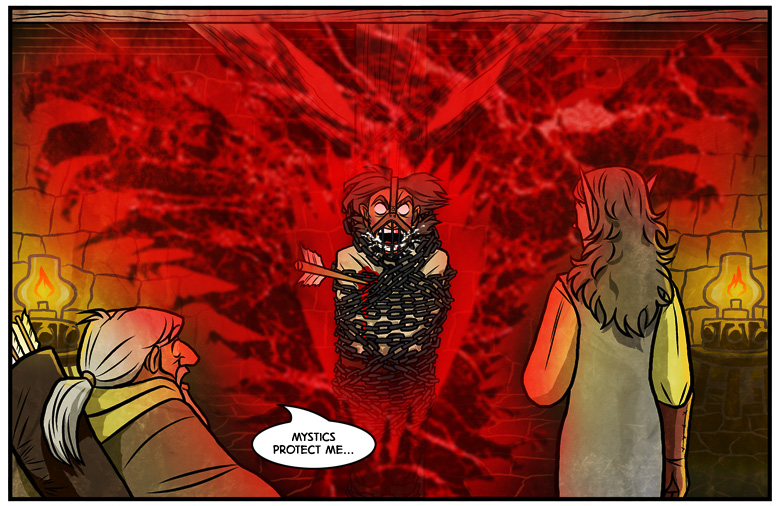

Let’s look at the RPG Sins. Heavily based on the Storyteller System used in White Wolf games like Exalted or Werewolf, Sins casts your persona as an undead being recently wrenched back to some form of self-awareness. Protecting humanity from an otherworldly horde known as the Brood, your character must maintain a balance between their humanity and their monstrousness, or else fall to ruin. It’s body horror and blood, hive-minds and howling from beyond the black. It’s 28 Days Later: the Masquerade.

It’s an interesting system mechanically, but similar enough to White Wolf’s systems that I won’t spend too much time focusing on the similarities and differences of the dice, interesting as I find them. Instead, I would like to focus on Sins’ world-building, because it’s also very White Wolf.

White Wolf is most famous for white-supremacist and anti-LGBTQIA+ — wait, no. As important as that issue is, I want to talk about what survives the company, rather than prop up a dead horse to beat: the “World of Darkness,” later rebooted as the “Chronicles of Darkness.” It is a world similar to our own but with vampires, werewolves, ghosts, etc. It is a darkly Gothic and brooding world, slowly dying as the ancient monsters (which you play as) deal with internal politics, hiding from humanity, and resisting the coming apocalypse.

One of the most interesting aspects of the World of Darkness is how powerful everyone is. Even at creation the most meager vampire or werewolf is vastly superior to a multitude of mortals. For higher ranks it can get outright ridiculous; high level characters can be world-breakingly powerful. Sins is similar; you may start out stronger than an average mortal, but you can become strong enough to command a legion of unstoppable undead yourself, or transform into a monster that can single-handedly destroy armies.

It would be easy to guess that the game is more pulpy than it is. Ignoring the established tone for a moment, when your characters reach super-hero levels of strength, it can be hard to imagine ever feeling scared of anything.

“No, it’s really easy! Just make sure whatever they fight is even stronger than they are. They’ll be scared of losing their character, and viola, you have a horror RPG, right?”

No, because RPGS like D&D and FATE also have challenges greater than the characters. Sure, fighting a dragon can be scary, but is it horrific?

Besides, doesn’t any amount of power thwart horrific intent? Horror cannot exist in tandem with power; if you do not fear death, where is the horror in a slasher? If you can control multitudes, where is the terror in the Illuminati? If you wield godly magics, would you run from anything less than a god? If your life is hell, why fear damnation?

What makes an RPG horrific?

Well, that’s a pretty hard question to answer. What actually is horror, anyway?

Darned if I know. Instead, let’s look at the easy answers: If we want to make the game-narrative horrific, there are the obvious story tropes. We all know how to have power outages, jump scares, and moaning zombies crawl out of the walls. A lot of systems use these tropes to turn non-horrific games into horror franchises: consider Ravenloft for D&D, the GURPS Horror book, or any of hundreds of horror modules for other games. That’s how you tell a horror story.

But if we’re looking at the meta-narrative, we can focus on dis-empowerment. To be afraid of something you must fear its ability to affect you, and power is all about controlling the world around you. It’s no mistake that Call of Cthulhu allows for characters no more powerful than your average 20s detective; and for every scrap of power you attain you lose an equal — or perhaps greater — piece of your humanity.

It’s not just Call of Cthulhu: players my age know to fear the ethereal Wraith, whose grip only caused minor damage but drained a full level of experience from their target. All XP, abilities, and HP associated with that level was gone, forever, unless you could afford an incredibly expensive Restoration spell.

So if horror requires disempowerment, is Sins not a horror game? What about any of the other World of Darkness systems, where you can tear apart ocean-liners, command millions, or change weather-patterns with a single thought? Can you become too powerful to ever be afraid again?

Let’s talk about ludo-narrative horror: both Sins and the World of Darkness recognize that power is relative. Whether it’s called Limit, Spite, Sanity, Humanity, or Morality, there is something in these games that you have no power over; it has power over you. In some cases it’s lost permanently when spent; a symbol of a character’s ever dwindling self-control. At best, there is no clear, simple, or reliable way to regain what was lost. You are on borrowed time, and every failure is another tick on the clock closer to midnight.

This is a possible ludo-narrative lynchpin, I believe, to horror in RPGs. As long as there is some economy or mechanic that is not only outside the players control, but consistently and permanently so, then the players will have a constant reminder, an imminent threat that hangs over their heads as the game progresses. It could be a sanity meter, unhealing hit points, or a Jenga tower. Will in Burnout Reaper is a perfectly horrific mechanic, turning the act of survival into self-abuse.

Disempowerment is another potentially dangerous subject in RPGs. As I said before, there are people who enjoy the feeling of being in control, who enjoy feeling powerful. As always, talking with your players is an important means for ensuring enjoyable play.

But we don’t, do we? We don’t talk about disempowerment in our games. At least, we never seem to talk about that one disempowerment. The pinnacle of disempowerment and sacrifice. Everything else is an economy, handled relatively easily…and then, with a string of particularly bad luck, we find ourselves sacrificing one final time.

Next time, we’ll talk about Death.