Cairn, and Empowerment

Cairn is, according to its website, quote: “an adventure game about exploring a dark & mysterious Wood filled with strange folk, hidden treasure, and unspeakable monstrosities. Character generation is quick and random, classless, and relies on fictional advancement rather than through XP or level mechanics.”

Aesthetically, Cairn is a fantasy D&D-like, with swords and spells and goblins galore. Mechanically, it’s an interesting mix of new and old-school rules. Random rolling of character stats is from the early era, when new characters’ long-term survival was neither expected nor reliable. On the other hand, its combat system is rather new, starting from the assumption that all attacks hit and the only randomness comes from a weapon’s damage dice.

Also, Cairn has no XP or leveling.

So how do you get more powerful? Because you need to get more powerful in an RPG, don’t you? If you never get more powerful, what’s to stop you from heading to the dragon’s cave right now? In both games and narratives, any overarching “problem” cannot be overcome by people at the start; They need to grow in ability, gain allies, learn more about themselves or the world, etc.

Mechanically, this is a state of low hp, limited money, and non-magical weapons. Narratively, it’s low information, resources, and insufficient preparation. Whatever kind of RPG it is, you are not able to just walk from the opening scene to the closing scene; there are obstacles in the way, obstacles you need to climb over.

Now sure, there are one-shots and one-pagers like Honey Heist or Stealing the Throne that don’t really have the time for characters to either “grow stronger” in a mechanical sense or “grow as characters” in a narrative sense, but Cairn is designed for both long- and short-term play. You can play a full-length campaign with Cairn, growing from a fresh-faced adventurer to a world-shaking avatar.

How does it manage that without XP or leveling? Cairn uses “fictional advancement.”

Usually in RPGs, character growth is a mechanical effect: you gain a level, and therefore more skill points, abilities, or assets. This is then represented somehow in the game-narrative, either by a promotion, further education, or just hand-waved as “practice.”

Fictional Advancement is a term for growth that goes in the other direction. The narrative defines the growth that is then given a mechanical effect in-game. Perhaps they find a new magic sword, have a training session with a swordmaster, or receive a divine blessing for their actions. They don’t gain arbitrary “levels,” but instead get more and better assets through play.

For example, a character desperate to end the ritual before a demon is summoned might drink the vial of dragon blood to keep the cultists from getting it. The GM might then decide that the character has been tainted by this dark blood, and can now breathe fire once per round in combat.

Or, a character might meet an engineer who is a genius with robotics, and give them both the fusion cell and the compensation to build a giant backpack-fist that they can strap onto their back. Now the character has three limbs, one of which is twice as strong as the other two, if prone to rust.

Or, after spending several weeks on a mountaintop with a guru, they get +1 to their attacks, thanks to their advanced training.

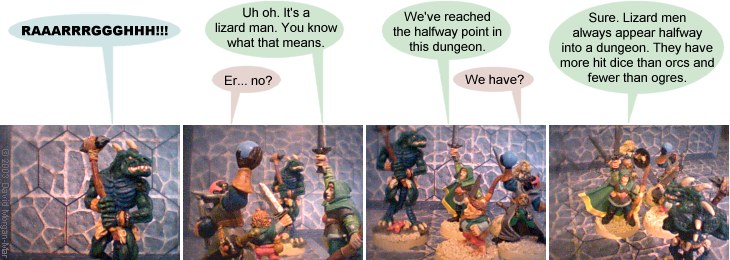

It’s been a point of contention among players since the beginning: experience point systems can sometimes result in a thief getting better at lockpicking after killing some orcs, or a spy getting more charming once they’ve shot enough bad-guys. If the ludo-narrative for an RPG is combat-focused, combat is how you got better at everything.

There are lots of methods to combat this, including giving experience for successfully picking locks or schmoozing, or using a “milestone” method, where you gain levels by reaching narrative points in a story rather than accumulating points through actions. Cairn embraces the method of leaving it entirely up to the players. If you want to be better at fighting, go get a better sword, take lessons, or find an ancient sword-maiden training book. You grow stronger because of your story, not arbitrary mechanics that then have to be explained by your story.

Because eventually your investments will earn you HP, allies, the secret word, the holy sword, whatever it takes. Then, everything that caused you trouble before is now easier to overcome. Eventually a sea of goblins is your early-morning exercise and your only failures are the unwelcome banana-peel that is rolling a 1. You have to find harder challenges, or else the game stops being fun.

The balance of power in a game is a delicate thing. You need to give players enough of a challenge that their ingenuity or ability is tested, but not so forcefully that even at their best their survival is unlikely. But if the challenge is “perfectly” balanced, then is survival really more than flipping a coin? But the more you tip the scales, the more randomness becomes the deciding factor in an otherwise sure bet — every growth upsets the balance and must therefore be offset, oftentimes arbitrarily, by an increase in opposition.

It’s kinda shaped like a sine wave. To put it metaphorically, players start off weak and will ultimately have to run from something stronger. Once they get strong enough they will overcome what they ran from. Through the next door will be something stronger that they have to run from again, until they get strong enough, and then the next door, and the next, and so on and so forth.

A small sine wave can hide that this is even happening. A steady increase in difficulty means that players are in perpetual struggle. A large sine wave, on the other hand, is more pulpy; characters see-saw back and forth between impossible odds and successful gambits.

And not to leave it unsaid, in some cases narrative handles all the heavy lifting. There is a difference between poking orcs with a wooden spear and thrusting at a dragon’s head with a magical lance, even if the number ratios and dps’s are comparable.

At the same time, narrative play can turn a conflict from handling numbers to handling situations. If you haven’t read LaTorra’s post on the 16 HP Dragon, I suggest you do.

Again, I think part of the issue with power balance and growth in RPGs tends to be type-mismatching. It’s easy to view empowerment separately, either from a game- or meta-narrative sense. Making characters powerful is different than making players feel powerful, and requires different techniques. I’ve played level 15 characters who felt drastically under-powered, and level 3 characters who felt like superheroes.

Players can disagree, too. Some think empowerment is a heightening of scope, where your character still struggles against their foes, but the foes change from goblins and orcs to demons and gods. Others think empowerment is a broadening of ability, where similar problems become easier to solve with an ever widening array of more powerful tools.

And, as any experienced gym-folk will tell you, we all lift different weights. The purpose of challenge is not to weed out the weak and sickly or to force everyone to gitgood; it’s to refocus RPGs on the game aspect, where victory is uncertain, failure is always a possibility, and it’s your choices that affect the outcome.

But what about the flip-side of the coin? What about dis-empowerment?

After all, that’s the other part of the sine wave, isn’t it? That moment when, flush with new keys to open all manner of doors, the characters realize this door has more teeth than they’re used to? When they realize the antagonist across the room has their own keys?

A feeling of dread settles on their hearts, their skin prickles, their brows begin to moisten…

Next time, we’re going to talk about horror.