Mothership, and Death

Set in space, Mothership takes its cues from the horror sci-fi genre; everything from Aliens to Event Horizon. Players familiar with Call of Cthulhu will likely be comfortable with the game’s sanity and panic mechanics, while the addition of classes and a tiered skill tree round out the flexibility of character creation. Space is dangerous, death comes easy, and if your character is lucky enough, they might make it to second level.

But I want to start even earlier than that. The Drain is a module for Mothership, a pre-built funnel adventure, designed to bring your characters from level 0 to level 1.

Players unfamiliar with Funnel Adventures might balk at that description. Don’t characters usually start at level 1?

Ever since their origin, Roleplaying games have centered on characters who aim to be heroes. They know how to use a sword, a spell or two, they can drive a car or handle a gun — they are at least able to face the preliminary dangers that await them.

As a result, the act of creating our characters in an RPG is a strange example of survivor bias: we know our characters will survive, at least for a little while, because that is the story we’re telling. But what about all those people who aren’t skilled, aren’t prepared, aren’t ready or able? We pay attention to the one who survives; what about all the others who never made it that far?

Enter the funnel adventure. Funnel adventures are modules designed to create your character, not by sitting down with the rulebook and talking it out with your GM, but by giving the players control of a large number of weak level-0 characters and sending them through a veritable meat-grinder to see which ones make it out alive.

There are lots of ways this can be used to create a character. Perhaps each success and failure adjusts the final character’s stats. Maybe each level-0 character is a different archetype. Sometimes the adventure is just a framing device, and the survivors are subjected to the same character creation after the adventure that anyone else would be. Whatever the mechanics, the meta-narrative is a charnel house. It’s death after death, until one body climbs to the top.

Funnel adventures are based on the emergent property of play during the early years of RPGs. Level 1 characters in D&D were not particularly sturdy. An errant die roll or an ignorant mistake could — and did — cause an untimely death for many a character. Then there was nothing to be done but roll up a new character and hope that this one survived longer. It was much quicker, easier, and less expensive to roll a new level 1 character than raise the previous one from the dead, and so more and more corpses piled up until one hero was lucky enough to survive.

So funnel adventures are horror stories, right? Well…no. If you think about it, how many people die in horror movies? Compared to the body counts in action movies, the horror genre is actually much easier to survive in.

But we’re not talking about extras or pedestrians, we’re talking about main characters. They may be more likely to die in horror stories, but those flippin’ cockroaches never die in action movies, do they? No matter how many slow-moving death-traps you stick them in.

Which brings us to one of the most important questions about death in RPGs: “Does Death matter?”

Narratively, the answer can vary per system. In Lancer, for example, technology is advanced enough that death is no more inconvenient to a character than being knocked unconscious. In D&D, raising the dead is pricey but not impossible. But what about meta-narratively? When I talk about death, I mean what happens if/when a character is permanently removed from play?

I don’t think it’s controversial to say that players can get attached to their characters. After playing multiple sessions, to have your character die because of a bad roll or even overwhelming opposition can be akin to having the protagonist die in the middle of a story — both narratively and personally unfulfilling.

Death is an interesting problem in RPGs, because while it is a useful tool for both sides of the game/story spectrum, neither side can use the tool effectively while also maintaining its value for the other.

On the one hand, death can be an effective moment in narratives — whether a heroic sacrifice or dramatic raising of stakes — but for death to be narratively significant it must follow narrative rules. That means characters need to die at low-points in the narrative; when the Warlord has sent their General to deal with these meddlesome do-gooders, not by an errant trap while they’re exploring a random tomb.

At the same time, a dramatic death scene is a waste of time if two scenes later the corpse is up and talking as if nothing happened. True sacrifice requires loss, and loss must be accounted for.

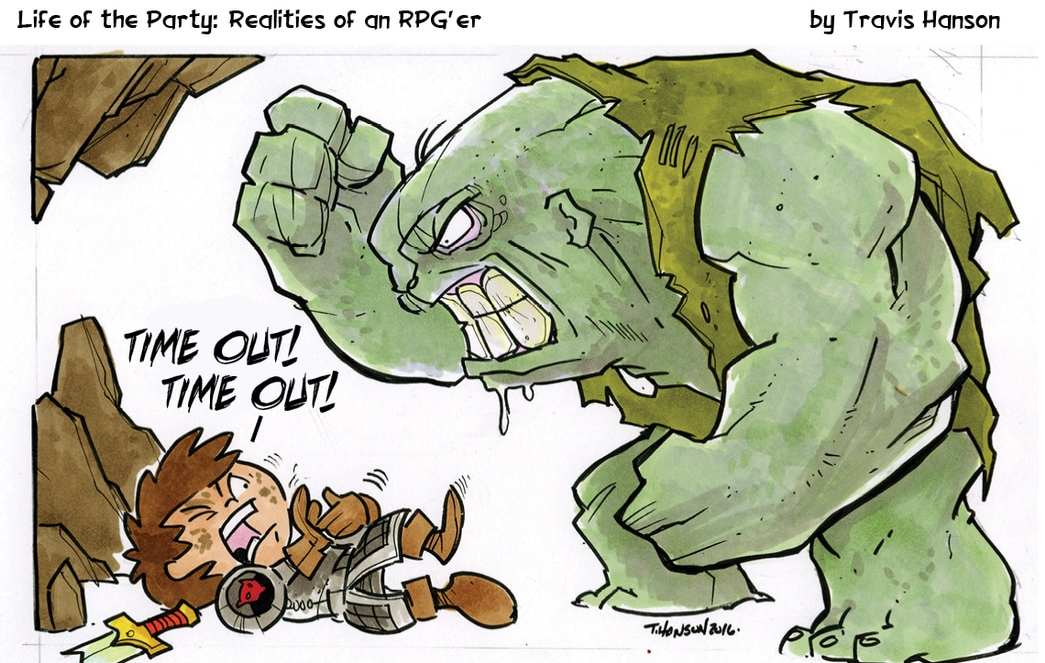

But a game without the chance of unexpected or unprepared for death is hamstrung when it comes to consequences. If death isn’t a possibility then there is little tension or anxiety when dealing with purportedly dangerous events. Check for traps? Why bother? Hordes of goblins aren’t threatening, because what’s the worst they can do to us, tie us up for a while before we break free?

Maybe. After all, death isn’t the only way to raise stakes in a narrative, so why does it need to be in an RPG?

Lancer, by taking permanent death off the table, encourages GMs to think of punishments beyond death for failure. Now that dying isn’t the ultimate punishment, losing the mission is. In video games we can reload and try missions again and again until we succeed — indeed, we have to — but in RPGs, failing at a task, combat, or any similarly dramatic moment is really only an opportunity for the story to go in a different direction. FATE asks GMs to see death as the easy way out. Even early D&D saw death at high levels as only a minor inconvenience, with clerics able to raise the dead at an admittedly high cost, or even ressurect lost characters from a pile of ash. This turned death into an expensive obstacle rather than the necessary end of a character.

So maybe player death isn’t worth including? If the meta-purpose of death makes the story unsatisfying, and the narrative-purpose of death makes the game uninteresting, then why have death at all?

Most games these days have adopted the meta-narrative excuse that “hit points” don’t represent any physical property of the character, but instead represent a multitude of ephemerals, such as fatigue, alertness, ability, and momentum. A character might never get touched by a blade during a fight but their hit points still dwindle as they tire, until at last they dodge too slow and a single blow takes them to 0 HP.

You can do the same with death. Perhaps “death” is merely being incapacitated, and is therefore survivable with an extended stay at the hospital. Some games use a “scar” model, which means that anyone who dies simply stands up at the end of the fight with a lost eye, a reduction in max hitpoints, or some other cost. Or perhaps a “dead” character is only captured and needs rescuing. Some people may enjoy the idea that their characters won’t actually die until or unless they want them to, while mechanically still having some punishment in the form of time, penalties, emotional trauma, or having to play a different character for a session or two until their main character is back in play.

Other players may care more about the mechanical game than the narrative roleplay and have little attachment to their characters beyond their strategic value, and that’s fine too.

And none of this is to say that there aren’t players who want their beloved characters to die if they pull the wrong lever. Loss is a powerful emotion, and there is nothing wrong with valuing that experience in a safe fantasy. Feeling pain because your beloved Thug died in a pointless and narratively unsatisfying way isn’t bad, and trying to remove that experience from RPGs isn’t necessary.

What isn’t fine is having a player who thought their character was going to avenge their father suddenly die halfway through the game, and then watch the GM shrug and demand a new character. What isn’t fine is realizing that your character is being railroaded into success, so all your efforts to survive is just wasting time.

Talk to your fellow players, people.

But all this is just focused on a single character being taken out of the game. What if every character is taken out? And I don’t just mean TPK; next time, I want to talk about what does it mean to lose in an RPG; or more to the point, if you can.