Call of Cthulhu, and The Rules Of The Story

You’ve probably heard of Call of Cthulhu if you’re involved in RPGs at all. Released in 1981 by Chaosium, the system is based on the works of H.P. Lovecraft. Usually set in the early 1900s, the game centers around investigators, artists, professors, and other similar protagonists of H.P.’s stories, discovering and hopefully thwarting the machinations of cultists, Old Ones, and horrors from beyond. It’s famous for having a high body count; do not fall in love with your characters, they will die or go mad with remarkable speed.

Okay…but…is that the point of the game? Because it’s kind of easy to survive in CoC. Here’s how you do it:

- Create a character with low Intelligence and Education.

- Get a gun, preferably something fully automatic. Make sure it’s loaded, and always have it drawn.

- Never go into caves, woods, graveyards, or basements.

Ta-da! As far as the game is concerned, you are now invincible. Why? Because for all our performed frustration over the stupid idiots who go down the steps with nothing more than a flashlight, horror movies wouldn’t work otherwise.

Genre is an interesting subject when it comes to RPGs. Heck, its an interesting subject period. Check out Ian Danskin’s three-part essay on Who Shot Guybrush Threepwood, specifically the last video, if you’re interested.

One of the interesting takes in that video is the idea that genre is a recipe for how an audience is supposed to engage with a text. The exact same calm and casual conversation over tea can be either heart-warming, suspenseful, or boring, depending on whether you are watching a romance, mystery, or comedy. Since “all art is interactive,” as Ian puts it, genre is a means of telling the audience how to interact. It’s giving them their script.

If we can call RPGs art then we can certainly say they are more overtly interactive than other mediums, so genre in RPGs must do the exact same thing. Consider the following situation: a group of characters open a door revealing a ten-foot by ten-foot room. In the middle of the room is a sobbing woman. What do you do?

You can do anything, remember. Your character is yours to command, and if you want to hug the woman, stab her, or close the door and walk away, it’s all allowed.

If you’re playing an action fantasy, you know that sobbing women in ancient tombs are usually vampires, so you should attack her. In a spy-thriller, she’s likely a prisoner of enemy agents. In a comedy game, her over-the-top wailings are most likely connected to a lost dog than anything else. How you play an RPG is dependent largely on the story you are expecting to tell.

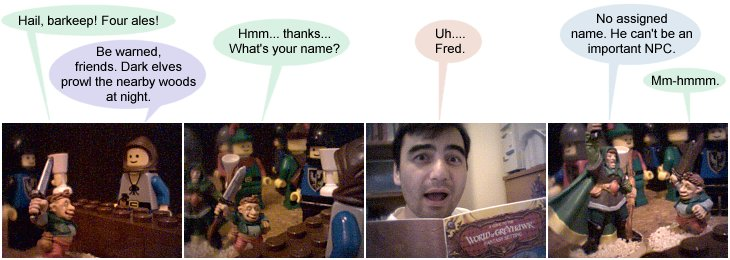

But doesn’t that mean you have to metastorytell? In a horror game, you know this sobbing woman is probably a ghost, but does that mean you can pull out your cross and begin the exorcism? Or are you supposed to ask her what’s wrong, get closer, and pretend to be scared when she looks up at you with empty eye sockets?

For all its mechanics, CoC is a narrative-focused game. You may know to not go alone into the basement, but your characters don’t. They can’t, because if they did, it wouldn’t be a horror game. The story would end in five minutes and everyone goes home unhappy. Play a game of CoC like that and you’ll never play another one. The point is to skirt and survive the danger. The players should be nervous children, testing how close they can get to the water before hopping back.

In film or literature, engagement usually requires a suspension of disbelief, but in RPGs it takes active participation. If we’re telling a story together, at some point you are going to have to have your character do something that you’d never do in real life, but is expected in the narrative. Whether its chasing after a monster or delving deeper into a cave without backup, you’ll have to follow the genre tropes.

And that’s before we even touch on the fact that any minor detail we’re made aware of must be important, otherwise why would the GM mention it? By virtue of a detail’s inclusion, it is made significant.

Now, an exceptional GM might be able to subtly encourage, if not masterfully manipulate the players into following the tropes that make the game work. That’s half of story-telling, if not more; making expected tropes of a given story seem natural.

It goes beyond just genre: storytelling itself has rules, and they aren’t like game rules. There’s Checkhov’s Gun, Conservation of Normality, Conservation of Detail, Economy of Character, and any number of expected narrative structures like foreshadowing, maintaining convention, low-points, moments of dramatic tension, denouements, and climaxes. Terry Pratchett made a career out of calling these rules out, parading them on display, and making them do tricks.

Which brings up another problem; there are tropes in the meta-narrative too. If the GM pulls out a battlemap and sets up the players on one side and a single “stranger on the road” on the other, can we honestly profess ignorance of the upcoming fight? If there are five of us, can we honestly say “we can take one stranger, no problem,” when we know the GM wouldn’t waste time with such an unbalanced combat?

If we know the tropes, are we supposed to embrace or reject them? If we know how the game is played, is it good to avoid letting those rules influence your decisions? Can you actually tell a story in an RPG game without metastorytelling?

Maybe not. Playing-the-Meta is a fascinating issue, at least for me, because it is so deeply woven into the medium. What drives me peanut-butter-pants-off-the-wall is how little people talk about it.

Metastorytelling is the perverse impossibility of ever truly getting lost in a story that we ourselves are creating. As a Writer, I can tell you it is difficult to avoid noticing every cliche trope that leaks into your writing. It may be hard to lose yourself in the magic after you’ve peeked behind the curtain. You might only notice how effectively or poorly the illusion is maintained.

But for all the squawking about metagaming being bad, the conversation only ever seems to center around players who don’t separate themselves from their personas enough. It has become, for all its noble intentions, a way of shaming those who care more about the “game” side of RPGs than the “role-playing.”

So to both launder their reputation and indulge the contrarian goblin in my brain, I would like to offer a defense of metaplay.

Because metagaming is just being aware of the meta-narrative’s genre. Metastorytelling is being aware of tropes, conventions, and the ebb and flow of narrative. Metaplay is placing yourself in the game next to your persona and not allowing them to go it alone. They many not know what you know and it’s hardly fair to expect them to succeed against an army of orcs without knowing their stat-blocks like you do, or recognizing that this climactic battle is the perfect time to pull out all the stops.

Metagaming and Metastorytelling are both ways of rejecting the separation between player and persona. When talking about Mythic Mortals, I suggested that this separation is primarily a narrative convention, designed to encourage verisimilitude. When talking about stats, I said that the intelligence stat relied on this separation while refusing to respect it.

This division between player and persona is a complex one, and one that few RPGs address head on. Most ignore it completely, while others subtly side-step the issue by either telling the players to play more than one character, like Godsend; or divide a few characters between multiple players, like Cobwebs.

Let me be clear about this: the purpose of discussing these issues is not to quantify “RPG quality” like some star-ranking review system. Rather, I hope to raise questions that you might ask yourself before beginning your next game. Give yourself permission to explore the aspects of our hobby that you haven’t looked at yet.

Exploration, after all, was one of the foundations of our hobby’s origins.

So what happens when the world that you are exploring is one you don’t know? Next time, I want to look at World-building.