MΣTΔ, and The Meta

MΣTΔ is, natch, a very meta RPG.

I have a bit of a problem discussing MΣTΔ as a game, because the interplay of meta content and non-meta content in the game makes it somewhat difficult to pin down exactly what is and is not meta about the game.

Okay, deep breaths, let’s start at the beginning: what is “meta” anyway?

Meta, as a prefix and an artistic concept, deals with an interaction between a discrete body of work — whether a painting, book, game, movie, or other medium — and the audience of said work. “Meta” occurs when both work and audience are both aware of and able to address the body of work’s existence and the external expectations of said work.

My, that’s quite an overly pretentious way of putting it. How about an example?

MΣTΔ — the game, not the concept — is about “MΣTΔs:” beings that exist only to embody physical forms across multiple universes. Transcending time and space, the MΣTΔs incarnate in different realities to experience different worlds, entertain themselves, and learn more about what makes them who they are.

MΣTΔs are, in fact, players of RPGs.

I mean, that’s what a MΣTΔ is, isn’t it? The players of MΣTΔ are MΣTΔs themselves, which are both extra-dimensional beings in the established game-narrative, and accurate descriptions of the players sitting around the table; the meta-narrative.

This is “being meta.” When the art tries to subvert your expectations for what it means to experience said art, it is playing with the meta. (This is, of course, a fairly shallow and colloquial definition of meta, and anyone with any extensive background in the subject will likely tear their hair out at my description, but it will serve for the moment.)

Even the classes in MΣTΔ play with the meta. You could be a Seer, based on being a GM, and arbitrate facts about the game world or roll on tables from corebooks from completely different systems. You could be a Slayer, who is playing a system-first combat RPG and gets the ability to manifest loot after killing things. You could be a Storyteller, who is playing a fiction-first game and can create completely new characters to swap between at will.

Or you could be the Strategist, a rules-lawyer who has the canonical ability to metagame.

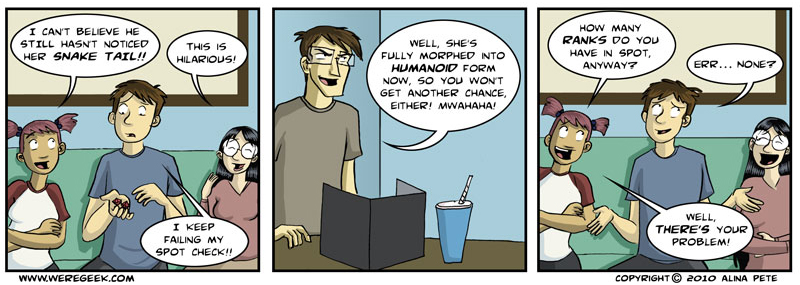

“Metagaming” in RPGs is the term for blurring the line between what a player knows and what their character knows. The simplest example is when one player is jumped by thugs in an alleyway, a second player currently having a hushed conversation in the pub suddenly says “wait here for a moment, I want to stretch my legs with an impromptu walk in this direction-ish, and I’ll pull out my gun just in case I run across any thugs and have to save any of my fellow party-members who might be fighting them. Just in case, you know?”

Players are at the same table, listening to each other, and hearing the whole story. Characters are not. Keeping knowledge that one group has separate from the other helps tell a more verisimilitudinous story. You may know what your fellow players are doing, but your character won’t until they meet up.

Some GMs go so far to fight metagaming by rolling for the players if there is something hidden they might notice. After all, asking for a roll to see if a character notices something tells the player there’s something to notice.

What’s interesting to me about MΣTΔ is how codified the meta is. Did you catch that I said the Strategist has the canonical ability to metagame? All of the class abilities I mentioned can only be used with the GM’s consent. Even in a game all about breaking the fourth wall of RPGs and playing in the meta, the rules still retain their control.

MΣTΔ encourages a kind of “safe” metagaming. There is a metaphorical second fourth wall erected beyond the first broken one. In a real way, the breaking of the fourth wall and playing in the meta is… not meta. It’s the opposite of meta, it’s diagetic.

This results in a structured and guided type of play that bends the rules just enough to address and comment on metagaming without directly embracing meta-play. There’s nothing wrong with that, it works well for what it wants to do.

And what it wants to do is make metagaming acceptable.

Because metagaming is bad. At least, that’s the axiom in the RPG community. Narratively, it breaks immersion and sacrifices the story for the game. Mechanically, metagaming is akin to using your hands in soccer; an obstacle for players to overcome, if not expressly proscribed in the rules. MΣTΔ had to make the meta diagetic, because the alternative would be poor play.

But here’s the thing: we can’t not metagame.

Let me give you an example. I played a game of D&D once with someone who was relatively new to the system; there was a lot that they didn’t know. Nothing wrong with that — we were all new to the game once — but then we came across a room with flesh golems in it. We got in real trouble early on with some bad combat rolls, so our novice friend rolled up his wizard’s sleeves and said: “guess I have to bring out the big guns. I cast lightning bolt!”

Those who know D&D’s flesh golems know that they are Frankenstein’s Monster pastiches. Naturally, that means lightning damage recharges them, causing them to speed up. After casting his spell, our flesh golem foes had become stronger. My friend’s ignorance of D&D stat blocks had made a hard fight even harder.

Now here’s the kicker: if we accept metagaming as a bad practice, it was we veterans who were playing wrong, not the novice. We knew the strengths and weaknesses of flesh golems, but our characters didn’t. We hadn’t read up on flesh-golems in the local library, and the last wizard’s tower didn’t have any monster manuals for us to sort through. This was the first time any of our characters had ever heard of these kind of monsters; why wouldn’t they throw powerful lightning bolts at them?

If metagaming is bad, should we make the game harder on ourselves because our personas weren’t supposed to know? A lot of players would hate that idea, the expectation that if our character’s ignorance could get them killed we have to push them towards it.

There is an aspect of early RPGs that we tend to forget; when the Monster Compendiums and Fiend Folios came out, these monsters were all new. No one knew that demi-liches stole souls or that mind-flayers ate brains. They didn’t know who was weak to what kind of damage, or which monsters could cast which spells. There was a level of discovery that isn’t always part of the equation anymore.

Some games even encourage metagaming. Old geezers like myself might remember the classic video game Dungeon Master. A dungeon delver game like Wizardry or Might and Magic, your characters cast magic spells by clicking on specific runes in a specific order. The interesting twist about this was that the manual did not give you a list of spells; the recipe for every spell you cast had to be discovered either through clues and notes in-game, or trial-and-error.

The first time you played the game, you didn’t know any spells. The third time you played the game, you might know all the spells. Magic in Dungeon Master was dependent on metagaming.

This same design ethos could apply to RPGs. You’re only “supposed” to cast lightning on a flesh golem once, and then you know better. Not metagaming would be like not looking at your hole cards in Texas Hold’em. You’re hamstringing yourself for no real reason.

So the obvious method of squaring this circle is to allow any level of metagaming so long as you can come up with a narrative excuse for it. “See, my character needs a smoke, so they leave the bar; and they don’t like people, so they head towards the dark alleys; and they’re a hard-boiled sort, so they draw their gun because it makes them feel more secure. It’s not metagaming!” This encourages viewing the game-narrative as not a story but a gimmick. Not only do you have to play a board game, but you also have to do it while making up excuses for why someone would take the actions that win the game.

Or, you can use the narrative solution of systems like FATE or Belonging Outside Belonging that encourage you to shoot lightning at flesh golems every once in a while.

I think Metagaming as a concept is a bit unexplored. I can’t say that metagaming is categorically bad, anymore than I can say anything is categorically bad. Sometimes it may be unavoidable or even desired. But even setting aside the theory that metagaming results in sub-par gameplay, I think there is another facet of metagaming that is as — if not more — important.

What about meta-storytelling?