Mythic Mortals, and Pretending To Be Yourself

Mythic Mortals is, quote: “an action-focused roleplaying game that lets you and your friends engage in over-the-top fights and epic battles. Inspired by The Avengers, 300, X-Men, Devil May Cry, and so many more; Mythic Mortals aims to bring that fun, explosive experience to the table top.”

The mechanics of Mythic Mortals — a narrative-focused card-drawing strategic-combat system — are certainly worthy of discussion, but it’s the next line in the introduction that is most interesting to me: “You and your friends will play as yourselves, suddenly granted incredible powers.”

One of the most foundational aspects of RPGs is the idea that you create an imagined persona to inhabit. It’s not really “you” who is saying or doing these things, but someone else. It is a mask that we wear, through which we can experience or empathize with a different point of view.

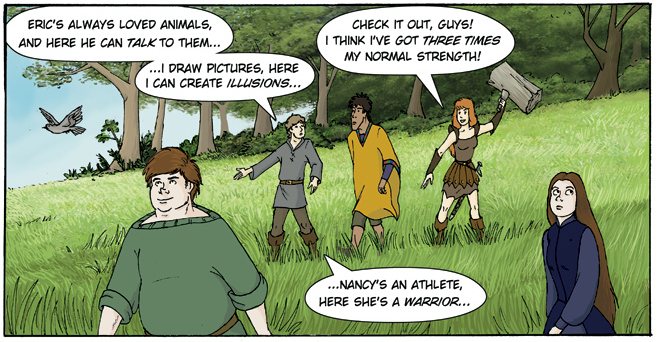

Mythic Mortals rejects all that. You don’t play a magical creature or an alien from another dimension, you don’t play someone with a carefully crafted backstory that ties into the main plot, you play…you.

You with powers, yes, gifted with supernatural abilities that make you capable of overcoming otherworldly threats that endanger the planet, yes…but that hero is nonetheless you.

And that is fascinating.

Most rulebooks have sections — or even whole chapters — devoted to players new to RPGs as a whole; people who might not understand terminology like “roll 2d6+3,” or “NPC.” These newcomers are given helpful hints: “Address each other by your characters’ names,” they suggest, “so instead of asking ‘Carla, what does Ellwyn do next,’ ask ‘Ellwyn, what do you do next?’” Players are encouraged to describe actions as though it was themselves doing the action.

On the other hand, the first D&D rulebook detailed an example of play so bizarre that I can’t even consider it quaint: The game suggests having a single “caller” who explains what the entire party is doing, thus:

Caller: “We’re walking north.”

DM: “Fifty feet up along the corridor there’s a door in the east wall. It’s five feet wide.”

Caller: “Halfling will listen at the door.”

DM: “He doesn’t hear anything.”

Caller: “The fighting man will open the door. He’s got his sword out, ready to strike. The halfling and the thief are right behind him.”

The example continues. It’s not even archaic, its…clunky. No names, just “the halfling.” “The thief.” “The fighting man.” (yes, fighters were called fighting men for a while. It got better.) What of the other players? Are they waiting patiently to be called on? Are they allowed to say “no, I’m actually not behind the fighter?” In this model, the characters are little more than figurines on a board: The magic-user, the top hat, the blue token, the meeple.

At the same time, separating players and characters has its value, especially if a player wants to play a character who is antagonistic towards others. A player who says “Thug’s feeling worried, so he’s going to try and throw his weight around and try to puff himself up, make like a big man,” is clearly better than a player just shouting “Wow, you’re all losers, step aside and let a real man’s man handle this.”

In my last post, I discussed how “playing a character” can sometimes be a blurred line. Characters aren’t playing a game while their players very much are. It’s natural, therefore, when a character does something rash or ineffective, for the other players to ask “why did you do that?”

Mythic Mortals doesn’t let you shrug and say “it’s what my character wanted to do.” Foregoing the fourth wall entirely, kicking the kayfabe to the floor, Mythic Mortals says “no, you are the person in charge here. Not some persona you made up, not a character from your wildest fantasies, it’s you. What do you think is a good idea?”

It’s at once freeing and limiting. No longer bound to the imagined choices of a character, you are instead free to be yourself, to explore not the thoughts of an imaginary person, but your own.

In the fourth episode of his demi-treatise Story Beats, Ian Danskin of Innuendo Studios asks the question: “what does it mean to act like a hero?” Media can make you sympathize with characters or empathize with viewpoints, but always with a fourth wall separating you from the decision itself. You can never be proud of yourself, watching Superman be a hero. You can never feel good about your own choices, reading a book about a brave person helping to save a town. You can only watch and be proud of them.

In video games, says Ian, that wall can be broken. Suddenly you can act like a hero, sacrificing yourself where before you could only feel sympathy. In RPGs, sacrifice, charity, heroism…almost any virtue can be made palpable. Characters can sacrifice themselves to allow others to survive. Assets are spent, choices are made, and our behavior affects the game and ourselves far more concretely than simply watching a movie or reading a book.

“Staying in Character” is a bit of a mainstay of RPGs. It’s usually considered bad form to hop in and out arbitrarily, but I think its a good question to ask — both of those who are comfortable with improv and those who’d prefer not to perform in front of their friends — is there something to be gained by just being ourselves?

This — coupled with my take on intelligence as a stat — may make it sound like I’m on the “you can only play yourself” side of things. I’m not, I see value in both sides, but I am not okay with just assuming that “playing a character” is something that can be done without some measure of examination.

And there is a dark side to this discussion; one that every RPG player quakes in fear of. Next time, I’d like to talk about the problems that arise when we weaken the wall between the imagined world and our own.

Next time, we’ll talk about metagaming.