King is Dead, and Being Given A Role

King is Dead is, quote: “A print-n’-play roleplaying game about a family of giants, their feuds, and a prophesy that may spell doom. Will you follow your father’s wishes and swear fealty to Branwen, or revolt and fight against the tide of destiny and take what you think is rightfully yours, or perhaps you will find another way?”

Mechanically, the game uses the AGORA system, which was designed for a game that (at time of writing) has yet to be released. The structure is fairly simple, with stats, jobs, (read: skills) and assets. Lots and Ego are methods for rerolling dice and getting bonuses, respectively. An interesting Quirk system allows you to take a -1 die on any roll that relates to a personality trait, in exchange for a +2 die bonus on a later roll that relates to the same trait. This, in essence, gamifies the narrative structure of a character “flaw” causing issues early on, only to be pivotal to success later in the story. All in all, its a pretty interesting system.

Let’s talk about the story: King is Dead comes with a full set of pre-built characters. This isn’t particularly unique; plenty of RPGs have pre-built characters that new-comers to the system can pick up and play without needing too much preparation. Creating characters usually requires a set of rules separate from those used to play the game. Pre-builts are a good method of highlighting different kinds of character builds, while also allowing newcomers to focus on game-play.

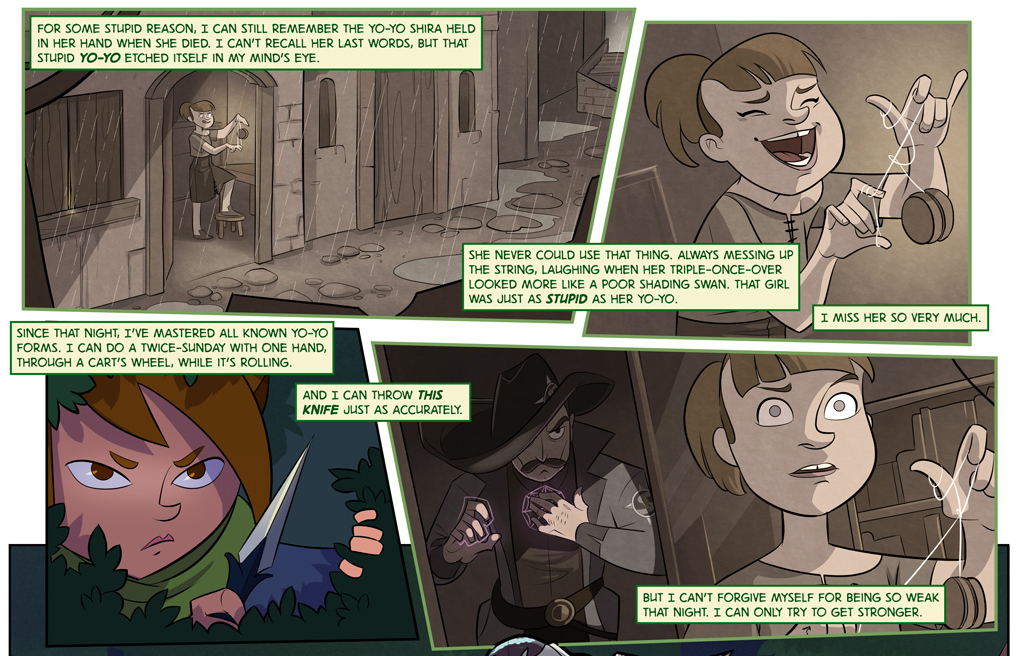

King is Dead calls their roster of pre-builts the “cast.” Make no mistake, this adventure was built with these specific characters in mind. They have backstories, motivations, and personalities that are directly connected to how the game plays out. The game-lore references them by name. You’re not here to make your own characters, you’re here to play a role.

What do I mean by that? Isn’t roleplaying and playing-a-role the same thing? Let me rephrase; you’re here to play a role that has been created for you.

Isn’t that a bit restrictive? Where does the player’s creative will enter the picture? King is Dead tries to deal with this by putting more “character” into their pre-builts than they expected a single player to track. With multiple creeds, habits, goals, quirks, and detailed backgrounds, the player can focus on the one or two aspects of the character that appeal and forget the rest. This allows each player to turn a pre-made persona into their own personal character while still maintaining narrative cohesion.

But no matter what happens with a pre-built character, it is never — on a fundamental level — your character. Making a character is one of the many fundamental aspects of an RPG. When we step into a fantasy, we generally want to do so in a persona that is tailor-made for us. For some, playing a pre-built character is in direct opposition to our reasons for playing RPGs.

Roleplaying a character is a more complicated thing than we give it credit for. When we make our own characters, we decide everything about them. What constraints we have are usually genre-, trope-, or tone-based. Pre-builts, on the other hand, force us to consider the behavior of a character we don’t know on such a fundamental level as we do our own creations. When we are given a role, we have to consider how that person would act. When we create a role, we have much more freedom in our behavior.

…Right?

Rolling with Rainbows is a Let’s Play podcast currently (also at time of writing) in their first season playing Call of Cthulhu. In Episode 21, the character Octavia, played by Jess, drinks some kind of Lovecraftian ooze. There is context to all of this, but none of it is as important as this line, spoken by Jess just before Octavia tips her head back.

“I was really hoping someone could talk her out of doing this.”

Now this here, this line, is a fascinating line. I love that she said it, because it encapsulates one of the biggest and thorniest problems that RPGs have ever had to deal with, especially when bringing narrative and player-responsibility into the mix. Namely; who’s responsible for the character’s actions?

Well, the player, right? Isn’t that the whole point of playing a role-playing game? You play a role. You do that, not the person on your left or right. There are whole unwritten rules about it: Don’t play someone else’s character.

That’s true… but…

In The Thermian Argument, Dan Olsen of Folding Ideas details a logical fallacy that is used to excuse problematic content in media: specifically, the fallacy that works of fiction are in some way “documentaries of what actually happened.” You may recognize this as kayfabe, the suspension of disbelief agreed upon by both actor and audience in Wrestling. It’s all acting, it’s all fake, it’s all scripted…but we pretend it isn’t, and we all quietly agree to pretend it isn’t because it’s more fun that way.

It’s not always conscious. A friend of mine fell afoul of the Thermian Argument while watching the second Hobbit movie, when she instinctively pointed at the screen and shouted “that’s not how it happened, they made that up!”

Of course they had. And, in fact, so had Tolkien, but in that moment the Hobbit book was more “real” than the Hobbit movie.

It is easy to forget with media that ensnares and enraptures us there is a creative intent behind everything you experience. Maybe there is an in-universe explanation for why things are the way they are in books, movies, etc…but those are fundamentally excuses. A creator can, in fact, create anything they want and explain it however they see fit.

Who decided whether or not Octavia was talked out of drinking the ooze? It couldn’t have been anyone but Jess. Why didn’t Jess say “sure, that talks her out of it, Octavia puts the ooze down,” if she wanted that to happen? You can make your character do anything, all it takes is finding a fitting explanation. Bad stories are the ones where these explanations and excuses aren’t hidden or explained well enough — they break the suspension of disbelief.

But RPGs aren’t just a story, they’re also a game. So what happens when playing your character “right,” causes problems in the game?

If we go back to non-narrative games, like chess or monopoly, we can explore the concept of “perfect play;” the idea that there is one set of moves or choices that would result in the most efficient or effective success over a challenge. Whatever the game, there is a “best way to play.” Games can be solved.

But even if we aren’t willing to go that far, we can see how roleplaying can fundamentally oppose being “good at the game.” Imagine a charitable character who gives away money that could be used for better equipment. Imagine a vengeful character who blunders through obvious traps for a chance to strike at their nemesis. The act of roleplaying encourages players to make their characters act in ways they know are unwise.

Octavia drinking the Lovecraftian ooze has not yet turned them into a ghoul, (third time’s the charm; at time of writing) but if it does, and that ghoul kills the other players, Octavia’s choice will have ended the game. Some players might consider this a fitting narrative end; you shouldn’t drink Lovecraftian ooze in a Lovecraftian horror story. Others might be upset that Jess “made a bad choice.” Not Octavia, Jess.

There is a cliche in RPGs about Paladins; the self-righteous lawful-good pricks who berate the other players because they keep killing all the goblins instead of urging them to convert to the light, as if killing the goblins wasn’t the point of the game. You’re supposed to roll your eyes at this character. “Just let us have fun and play the game. Don’t let your character spoil it for everyone else.”

But that’s an absurd sentiment for a lot of players, akin to “don’t play the game so we can all play the game.”

Perhaps this is getting too far down a rabbit hole. Maybe we can say that if you create a character who, in playing sincerely, ruins everyone else’s fun, you have created a bad character. Maybe it’s the players’ responsibility to make characters who actually want to play the game “right,” whatever that means.

Or maybe a group of players really enjoys having a Chaos Muppet around to mess things up. Maybe they like kicking over sandcastles, throwing pies, and lighting things on fire. Is it still playing the game wrong if everyone agrees it’s okay?

This is a long-winded way of asking the question: Can narrative suspension-of-disbelief exist in tandem with a game, or are these two aspects always at odds? This separation of Player and Character is a difficult spectrum to walk at the best of times.

Next time, I want to look at one obvious and drastic solution: doing away with that separation all together.