Runaway Hirelings, and Imaginary People

Runaway Hirelings is a comedy RPG about the squishiest and most inconsequential characters in the whole of the RPG medium: the hireling.

Hirelings served a very specific role in the early era of dungeon-delving RPGs. Players often found themselves lacking certain abilities: perhaps no one was playing a lockpicking thief, or they needed some method for carrying and extracting all the loot they scavenged from the dungeons. One of the original uses of Charisma in 1st Edition D&D was to limit how many hirelings you could command at once, and how likely they were to stick around. At higher levels you were gifted a stronghold along with a specific number of followers that you could bring along on adventures, to help mitigate the rising difficulties of the dungeons.

They were, in all practical senses, red-shirts.

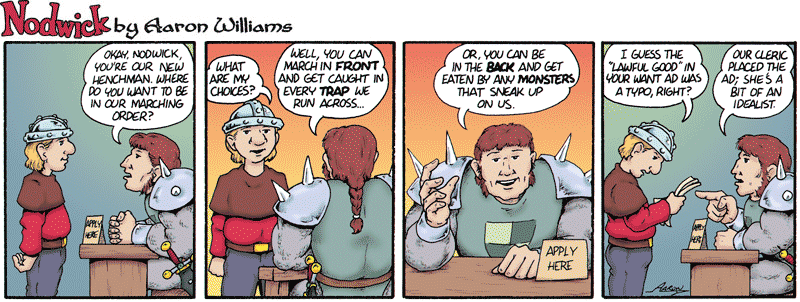

The joke is that hirelings check for traps by springing them, are perfectly shaped bait, and can carry everything you find on their backs, no matter how heavy or unwieldy. They had to be tools, because in the olden days, when each player could get anywhere from 2 to 12 apprentices hanging around, creating deep and multi-dimensional personalities for each one simply isn’t possible.

In Runaway Hirelings, the players engage in a narrative reversal and, quote: “take on the role [of] a hireling whose boss has died leaving them in the final room of the dungeon. They now have to make their way out of the dungeon without any heroes to defend and fight for them.”

The game’s intended tone is obviously comedic, but I’m struck by how easily it could be horrific. Hirelings are never as powerful as their patrons and are devoid of the many useful abilities that keep PCs alive. The game’s reversal of fortune sees drastically under-powered characters struggling to survive as they flee a dangerous dungeon. We can laugh because hirelings aren’t people, really. They’re archetypes and caricatures. They’re clowns, and clowns never really get hurt.

What are NPCs, really?

If they’re not hirelings or tools, are they extras? Assets? Obstacles akin to monsters except it’s not morally acceptable to kill them? Some are either tokens to be rescued or static quest-givers who exist only to provide options for adventure. Each NPC could become a significant ally or foe depending on how the players treat them. If you’re playing a mystery game, NPCs are significant plot-points, as much a part of the puzzle as a tiled-floor room or engraved poem.

An interesting question naturally follows: whose responsibility are they?

The easy (and common) answer is “the GM,” but that’s not the only answer. Some RPGs encourage players to play NPCs if their primary character is not in the scene. Some systems focus on a single character, rotating the PC and the NPCs among the players. Many GMs hand important NPCs to visiting players for a session or two.

What if hirelings could be played by anyone at anytime? What if one player plays multiple hirelings, whichever ones might be in a given scene or session? If you put aside the assumption that “players play only one character while the GM plays everyone else,” you can hack together some interesting options.

But hirelings are a specific kind of NPC. What about NPCs more generally? If you can play NPCs as readily as PCs, then what is your goal when playing an NPC? A different goal than playing a PC, naturally: NPCs aren’t main characters, while PCs certainly are. An NPC exists not to guide the action, but to provide obstacles, assets, or structure to a scene. They’re there to support the main characters.

But isn’t that what you want your fellow party-members to do? Support you, like you need to support them?

Are PCs people in their own right, or are they just tools for the players to advance the story? If a hireling is mechanically an asset, isn’t a PC the same? Looked at that way, you could see every ability, stat, item, and clue as a “means of narrative support.” A hireling means you don’t have to carry all that gold yourself. A sword means you don’t have to beat a goblin with a stick. A high dexterity means you can open locks that you couldn’t otherwise. A stolen letter means you know where the kidnapped noble is being held and you don’t have to go stumbling around looking for them.

The idea of “main characters” is also a bit of a monkey-wrench: In narrative RPGs there often comes a time when “the camera focuses on one character.” Perhaps it’s the climactic fight with their nemesis, or an estranged lover comes calling. Maybe they snuck out of the inn while everyone else was sleeping. Think of all the times your character has been in a situation where they had lesser stakes in the scene when compared to a fellow party-member. Think of all the times it was their scene to play. When it was their turn to defy their inner demons or give the rousing emotional speech.

What did you do? Did you give a rousing speech too? Were you just an asset? A tool to help advance their story? Were you an NPC?

The fact of the matter is, one character sheet is the same as any other. Sure, NPCs don’t get as many abilities or items or possibly even stats, but every character is ultimately nothing more than a list of statistics until they are played. An NPC could be played as richly detailed and multi-dimensional as any PC, or a PC could be little more than an asset for another player to tap. How you play a character can sometimes matter more than what the character is.

So how do you “play a character right?” I’ve seen players get hamstrung with decision fatigue as they try to juggle backstory, narrative structure, and the immediate situation, all hoping to find “the right answer.” I’ve been that player. I wonder if the idea of playing characters “right” can limit us.

When playing a character, is the question “what would they do in this situation” a good one? There is the contrary opinion that your role as player is to find reasons for characters to do what they “need to do” for the game; if you think your paladin would arrest your party’s thief and turn them over to the guard, your job is to work out a reason why they don’t, not force your fellow player to make a new character while their thief is serving ten-to-twelve.

I mean, you’re in charge of your character, right? Can you make them do anything?

Sure, you could. You could say your steel-eyed detective searching for redemption suddenly tosses his gun to the cultists and says “eh, Shub-Niggurath couldn’t be worse than polio. Let’s see how it goes, yeah?” But at the same time, no you can’t. It flies in the face of tone, of character backstory, of the point of the game.

So you must have some responsibility to play your character “right.” Perhaps that means accepting genre tropes, or maybe it means compromising your character’s motivations if they oppose the game’s goals.

But how much flexibility is too much? Maybe you can’t toss your gun to the cultists, but how many hard-boiled detectives decide they’ve had enough bloodshed and hang up their badge to go drown in whiskey until the nightmares end? That would still end the game; it’s the same thing mechanically, just with a different narrative excuse. Is there a point where even a character’s narratively justified actions are not acceptable?

If we boiled it down to the “what happens next” question, we can see two options: Either characters are imagined beings with motivations and goals that dictate action, or they are costumes we put on as narrative explanations for what a 16-to-hit that deals 18 slashing damage “looks like.” Either the story and the game shift in accordance with our character’s actions, or our characters shift in accordance with what the game or story require.

Fundamentally, we can ask the question “are you supposed to play a character or play a game,” and that’s an important spectrum to explore.

That said, let’s take it one step further. Next time, I’d like to talk about what happens when playing a character is the game.