GURPS, and the RPG War

GURPS is technically not an RPG, but an RPG System. It’s a distinction without much of a difference; an RPG is at once distinct-from and inexorably-linked to the ruleset used to play it. It could be said that D&D is a system, while settings like Greyhawk, the Forgotten Realms, or Ravenloft are the actual RPGs.

At the same time you could call Greyhawk a game setting, and say that The Keep On The Borderlands module that you’re playing is the actual RPG. Or you could call The Keep On The Borderlands a pre-built adventure, and it’s not until you and your friends are sitting around a table rolling dice that there is an actual RPG, but that’s mostly a matter of taste.

GURPS stands for Generic Universal Role Playing System. Systems that are Universal or Generic are sets of rules designed to create characters and model their abilities without placing any restraints on the game’s story or genre. While D&D is designed to play fantasy games with wizards and ogres and the like, you can use GURPS to play fantasy games, sci-fi games, horror, pulp, or any other genre you like.

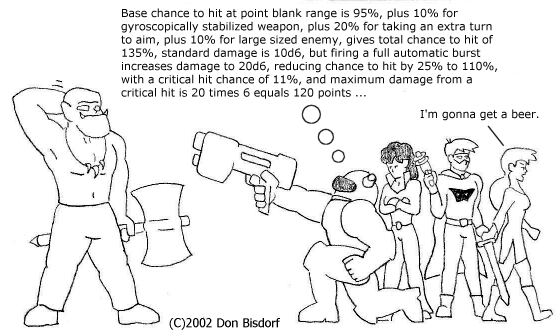

Figure 1: Some people hate math. Others play GURPS.

GURPS isn’t the only Universal system out there. There’s FATE, GUTS+, Ellipses, Omnimyth Fables, and Solipstry, just to name a few, and all of them provide a set of rules designed to adapt to any genre, tone, style, or story you care to play with.

GURPS does this with a simple mathematical model: characters are given a number of points to purchase stats, advantages, skills, etc. If you want to do something in-game, you roll 3d6, add them up, and compare the result to your chosen skill. Bonuses and penalties are added or subtracted due to situational effects, difficulty of the action, applicable advantages or disadvantages, etc.

There is a big difference between Universal RPG systems and the alternative — let’s call them Bespoke systems. Bespoke systems are created with a specific setting, genre, or narrative structure in mind: D&D is for telling high-magic fantasy stories, Call of Cthulhu is for cosmic horror games, etc. Universal systems, on the other hand, are designed to tell any story, play any game, independent of setting or genre.

But Universal Systems don’t all work the same way. Consider another Universal system, FATE (originally FUDGE Adventures in Tabletop Entertainment, now just FATE). In FATE, your character has five “aspects,” each of which describes the character’s qualities, such as “biggest strongman in the circus,” or “a traumatic past from time in the military.” Your character also has a set number of skills. If you want to do something, you roll four FUDGE dice — three-sided dice with faces of +1, -1, or 0 — and add the result to your skill. If you want to boost your result, you can look at your character’s aspects; if there is a reason being the “biggest strongman in the circus” might help, you can invoke it for a +2 bonus.

GURPS is all about numbers, rules, and simulations of actions through dice. If you want to be a four-armed insect-cat hybrid with a cybernetic leg and access to the Third Circle of Star-Magic, there are rules for each of those elements and they combine together to create a unique dice-based model for how such a character would function in a GURPS game.

FATE, on the other hand, cares more about narrative, discussion, and agreement between players and their view of the story. For example, one of your character’s aspects might be “four-armed insect-cat hybrid with a cybernetic leg.” What does that mean? Whatever the players and story make it mean.

As I explained earlier, roleplaying was born from two parents — Wargaming, and Fantasy books — and each has had its own impact on the medium.

Wargaming is a game, and games are about rules. You might win or lose, and you can only do what the rules permit you to do in the manner they permit you to do so. If you don’t, you are “breaking the rules” and the game doesn’t work.

Fantasy books are stories, and stories are about imagination. You can do anything that the established narrative does not prevent you from doing. The only rules are established in the world of the story, and if they aren’t followed our emotional investment is broken.

Now obviously, this can cause conflict. If someone wants to play a game, they might chafe at needing to maintain a coherent narrative: “I want to win, why do I need to invent a reason for why my space-captain wants to win too?”

At the same time, if someone wants to tell a story they might grumble when the rules provide stricter guidelines than they’re used to: “Why can’t I tackle the bartender to the floor to protect him from gunfire unless it’s my turn? Life doesn’t happen in turns!”

Now, long time RPG players may insist these two sides can be pleasantly blended together by mindful players. I agree. But, can any of us actually claim to know what the perfect balance is? And — more importantly — agree?

This is why we have arguments over wanting to “role-play instead of roll-play.” We have rule-mongers who cite chapter and verse to demand the right to roll dice to avoid important plot-beats. We laugh about the idea of “winning an RPG,” while rolling our eyes at “sub-optimal builds.” We have the drastically different design ethos’s of each edition of D&D. We have hundreds of pages of world-building that get tossed aside when a GM comes up with a cool idea, and fudged dice rolls that keep characters from being killed in the final showdown.

Imagine spending hours learning the interplay between a system’s rules and edge-cases, studying different abilities and creating a character build with the skills and powers you’re excited to play with…and then the GM wants you to improvise what your character says to get past a guard. You’re not as smart as a wizard, nor charming as a bard…but you have to think up something smart and/or charming to say? Do you have to lift a battleaxe too? Why have rules at all if what’s important is whether you can invent something that the GM subjectively thinks is sufficiently cool? That’s not a game, its a story being written by a popularity contest.

Alternately, if you know your character inside and out, with three-hundred pages of backstory, and have devised the perfect thing to say to put this pompous noble in their place, imagine being told that your creative input doesn’t matter, and the noble laughs in your face, all because your die came up 3. Imagine being told your well-trained ninja trips over their own feet and gets spotted by a lowly goblin, all because the rules say so. That’s not an RPG, that’s snakes and ladders.

Why should RPGs have dice and rules? Because playing pretend just isn’t fun. There should be limits, or else the game is over the instant someone pulls out their everything-proof shield.

But strategy games just aren’t fun; they’re boring math problems, and dice don’t care if they kill Frodo at the steps of Mount Doom…or even all the way back at the Prancing Pony, and I defy you to defend that narrative choice.

But saying “I kill the dragon with a magic sword” isn’t satisfying. Success via narration is a victory that hasn’t been earned, it’s been claimed. Satisfying challenges need to be resolved through one’s own efforts, not because the plot says “the bad guy has to die at the end.”

But it doesn’t make sense that my Level 15 wizard, who can summon demons with a snap of their fingers, can fumble a die roll and suddenly the barbarian knows more about this magical fungus than me. If it’s all numbers and chance, if the established narrative doesn’t directly affect and influence the game, why have narrative at all?

Roleplay is the twisted amalgamation of these incompatible concepts into a fractured whole. Discussions, arguments, and flame wars stretch through the hobby’s history on these subjects, and there is no way I’m going to be able to “solve” the conflict here.

Come to that, is there a solution to this conflict? A platonic ideal that synthesizes the dialectic? Are RPGs doomed to be a failure?

“Doomed to be a failure” is a bit melodramatic, no? We all agree this hobby is supposed to be fun, and if we’re not having any, we’re adult enough to be able to have that conversation with the group, right?

Perhaps. Or perhaps you’ll look around and see everyone else having fun, and you’ll decide the game you’re playing is fun enough, even if it wasn’t what you really wanted. Maybe you’ll tell yourself “that’s how the game is played.”

Too often I see people talk about “the right way to play,” when really all they are describing is a different way to play. One sided discussions become axioms while fiercely opinionated diatribes fill the discussion threads like yellow mold…and that’s okay. I’m opinionated too. I’m sure there are things I will say that make you bristle, just as I hope some things will make you nod.

But each reader will nod and bristle at different times, to different things, and that is an important part my thesis: If RPGs are “doomed to failure,” it will only be because we want RPGs to be everything at once. I don’t think they can be. I personally think this struggle is a foundational spectrum of the medium itself. Different kinds of RPGs are played by different kinds of gamers for different reasons, and to ensure that our games run smoothly and pleasantly for everyone, it behooves us to figure out exactly what these differences are.