Blades in the Dark, and the Two Narratives

Richly Gothic in tone, Blades in the Dark sees you and your fellows playing scoundrels in a wrought-iron steampunk city, working together to score heists, claim fortunes, and establish yourselves in positions of power in the city. The world is well designed, providing a fertile ground for intrigues, cloaks-and-daggers, and unseen dangers. Character design is detailed, including character sheets for each individual as well as the gang as a whole. You pick your backstory, select your class, put points into your skills, and set out to make or take your fortune.

There are many things that set Blades apart from other RPGs, but there is one specific part of the ruleset that I want to highlight: how the game handles action checks.

In most D&D-likes, if you want to do something, you have to roll dice to see if you can roll over (or under) a number chosen by your GM. If you do, your character succeeds at the task, while if you don’t, they don’t.

In Blades, on the other hand, if your character wants to do something, you roll a certain number of d6s and take the highest rolled number. If the highest is 6, you succeed at your task. If it’s a 4-5, you succeed with an added complication, an unforeseen hitch that causes trouble for your plans. If your highest die is 1-3, then things “go wrong.”

Does “go wrong” mean that the character fails in their task? Maybe, or maybe not. Maybe they fall off the wall, or perhaps they successfully climb in through the window right next to the guards on patrol. Maybe they break their lockpicks, or maybe they manage to pick the lock but now alarms are sounding everywhere. Maybe the guard elbows them in the stomach, or perhaps they cut the guard’s throat but now the whole constabulary is on a manhunt for the player.

This is a fierce devotion to a “fiction-first” ethos. What is fiction-first? A very good question, because no one seems to know.

Well, no, that’s not fair. Everyone knows what fiction-first — or sometimes fiction-forward — means, but like most colloquial idioms, it is quite the amorphous term. Look around and you’ll see a few generally agreed-upon principles about what makes a game “fiction-first,” but much like sandwiches, we don’t have an official definition yet.

Now, yes, we could pull Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart to the microphone to repeat his “I know it when I see it” definition, or we can once more drag Socrates and Euthyphro to their podiums and start debating whether we actually know anything at all, but that would take a long time, and likely be no more productive than simply asking: what does a fiction-first game play like?

Playing an RPG demands imagining a whole different world than our own; A constructed reality of invented people, history, and physical laws. We’re not just the blue token or the top hat, but Thug the Barbarian; a person with high strength, low wisdom, thoughts, feelings, and motivations separate from our own.

So with these two separate and established realities, how do they interact?

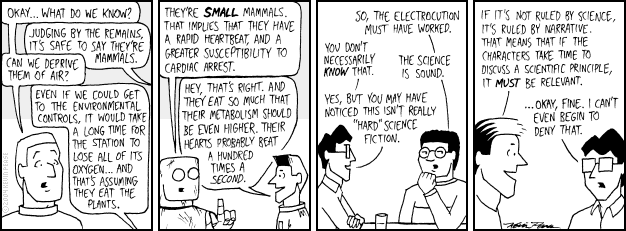

Figure 1: Never thought half my whole thesis could be summed up in one comic strip, but here we are…

If we rely on a fiction-first interaction, our created world unfolds through the laws of narrative; we focus on the laws of the world and let the rules of the game be of secondary concern. At best, the rules are there only to provide guidance and structure to our creative impulses. The story prompts what happens next, the rules then tell you how.

The basic example of fiction-first might be a magically flaming sword. This sword might give “+2 burning damage” to your attacks…but what happens if your character uses it underwater? In a fiction-first game the laws of the world trump the rules of the game and you’re swinging nothing more than a waterlogged stick of iron.

So, what would the antithesis to fiction-first be? I have been unable to find a communally agreed upon term for a “not-fiction-first” game, so I humbly submit the term “system-first.”

System-first gaming, as a contrary to fiction-first, devotes its attention to the system’s rules and mechanics as the primary means by which we interact with the imaginary world. The rules and dice tell us what happens next, and the story serves more as an explanation or a description.

In a system-first game, the rules say you get +2 burning damage for using a magical burning sword. If there are no rules about the sword not working underwater, then you get that damage no matter what. Maybe you can justify it as magical fire that burns even in water, but unless that flame also starts boiling the water around you, that’s just flavor to explain a system-first ruling.

Another good example is tripping people during combat. In a fiction-first game, you can try to trip an orc if you’re in a narratively suitable position to do so. If you’re tied up on the ground and an orc runs past, you could just stick out your legs and the orc might trip. In a system-first game, on the other hand, being “bound” and “prone” might prevent you from knocking an orc “prone.” Or, you might not be able to do anything because its not your turn.

Being unable to trip someone who is running past you may sound silly, but now consider how silly it might sound for your enemy to automatically kill one of your soldiers in Warhammer because “they had removed their armor to take a piss.”

So perhaps we use the loose definition; that fiction- and system-first decide whether the constructed narrative or the established ruleset is the primary source of “what can happen next.” After all, what happens next is always the most important question to ask in an RPG, and whether you first imagine the scene in your head or flip to the “available actions” in the rule book is as good a distinction as any.

Perhaps a more simplified definition could be that system-first gaming relies on the rules of the system, while fiction-first gaming relies on the rules of the story.

Now I could stop there, but the fact that there are two methods of divining “what happens next” suggests that there are two kinds of narrative in RPGs.

Let’s call them the Game-narrative and the Meta-narrative.

Game-narrative is perhaps the most obvious and easiest to understand. If you wrote a book based on an RPG you’ve played, what would you put in it? Your characters, what they did, what they said, descriptions of buildings, dungeons, and starships…things of that nature. The story that you and your fellow players are creating, the world, the plot, the action; everything imagined is the game-narrative.

Meta-narrative is, on the other hand, the story about you playing the game itself. It’s the story of your friends discussing rules, making judgments, talking through strategies, and not being able to roll above a seven this whole night. If game-narrative is the story of Thug the Barbarian and Wizer the Wizard who go kill the dragon, meta-narrative is the story of playing Thug and Wizer.

Now, what’s important to note here is that every RPG has both a game- and a meta-narrative, and can use either as its primary directive source. Fiction- or system-first is a descriptor of gameplay, not system structure. Rules are value-neutral; if you wanted to take the math-and-rules-heavy GURPS and play it fiction-first, that’s possible.

Of course, that doesn’t mean that systems can’t lean in favor of one or the other; Blades in the Dark — despite having a plethora of rules for stress, action rolls, resistance rolls, Heat, Coin, building a lair, reputation, XP, and more — encourages a fiction-first mindset with its dice. Whenever you roll, you are not just testing to see if a character does what they want to do, but what direction the narrative goes in.

Are these two styles of gaming incongruous? No, of course not. As with all things Binary, you should be immediately suspicious: especially when it comes to roleplaying, we live in mixtures of gray. Some people want to play make-believe with a little bit of structure. Some people want to play wargames with just a hint of narrative. Some seek a perfect blend, and others just want to spend time drinking and munching chips with friends. It’s all valid, but it’s not all the same game. Expecting one and getting the other can create intense friction. Fiction friction, if you will.

If you think you’re playing a system-first game, fiction-first can feel like cheating or railroading — forcing things to happen that the game wouldn’t allow otherwise. If you’re trying to play fiction-first, system-first can feel like saying “no” in improv, or someone pulling your character sheet out of your hands and playing your character for you. Neither is a fun experience.

But there is one more narrative that exists in RPGs; a third entrant into the running. Next time, I’d like to talk about when the system itself tells a story.