Revels in the Heavenly Hall, and FKR

Revels in the Heavenly Hall is, quote: “a game of violence without dice, powered by autonomy and collaboration in a one-shot framework that lets you sketch out a battlemap, arrange fighters on it one by one and then smash them into one another with reckless abandon. Its aim is to simulate tactics — not only good tactics, but awful ones too; ones that you would be ashamed to have thought of in a setting where the stakes are high and the story hinged on you being good at much of anything.”

Tactical combat is common in RPGs. Most of the early progenitors of the hobby had battlemaps and painted miniatures to move about, modeling our violent encounters. A lot of RPGs focus on tactical combat: There’s Lancer, yes, and 4th edition D&D, but there’s also Trespasser, Gubat Banwa, Strike!, Torq, Skirmish, and more.

The alternative is usually to rely on the “theatre of the mind.” There may be a sketched map, maybe some tokens, but the action is narrated rather than codified in lead miniatures moving across grids or hexes. Some games allow for both; GURPS, for example, has rules for hex-combat without requiring it.

So where does Revels in the Heavenly Hall fit? Well, Revels does something fascinating: it uses a kind of “tactical theatre of the mind” system, blending the hard system rules of tactical combat with the free fiat rules of narration and consensus.

To play out combat in Revels, you draw a map and describe the given-circumstances. Why is the combat occurring? What are the stakes? Who is on which side, and why? Once you’ve finished, the different sides take turns introducing pieces to the map and describing their actions. You could use tokens if you wish, but it’s just as viable for you to use your pencil to draw arrows and circles to mark where different pieces “are.” Really, the map is little more than a reference. As the fight progresses, the sides employ their own tactical and strategic moves in their attempt to succeed at their goals. There are no dice; conflict is resolved through discussion and player judgment.

Let me repeat that. There are no dice.

This will either fascinate you or horrify you, depending on your particular interests. Tactical wargaming is traditionally grounded in rules, whether you’re playing Warhammer 40k or Brikwars. Warhammer 40k, in fact, has no less than twenty separate full-length rulebooks for the different main armies you can make, and there are any number of side factions, supplements, and house-built units that make each army you create — and fight — unique. It works because the combat system is full of rules that clearly state how to move, attack, how to structure a turn, when certain things can and cannot happen…it’s all codified. It’s all fair.

Most all tactical play is like this, centered around a clear set of rules that all teams abide by. Any units’ unique ability is really just a small exception or modification to an otherwise universal rule. Indeed, the concept of tactics and strategy relies heavily on what will or won’t “work,” which likewise relies on what the rules allow.

At least, that’s how most wargames work.

Revels has neither dice nor stats. No unit speeds, no accuracy ratings, no meters for morale or supplies. It’s all narrative. Revels isn’t the only strategy game like this, either. There are also games like De:Throne, and Lo! Thy Dread Empire which are definitely tactical, but forego the chess-like battlemap and miniatures, relying on the theatre of the mind instead.

To have a strategy game without dice, without rules, without miniatures…is it even a strategy game anymore?

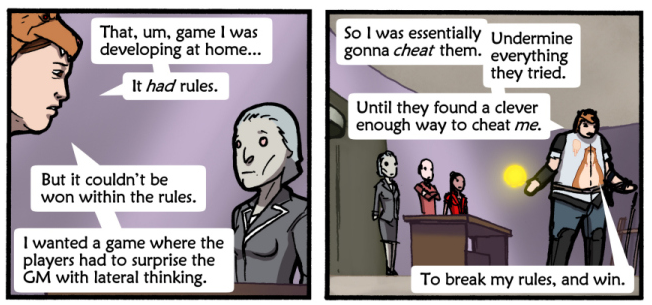

It is. I know it is, because there is precedent that goes all the way back to the 1800s. It’s called Free Kriegspiel. Similar to OSR, FKR (Free Kriegspiel Revival) is a movement devoted to the idea that rich gaming experiences, tactical and otherwise, can be had entirely with rulings rather than rules. What are rules, after all, but pre-established rulings? It’s judicial precident. It’s established law.

But every RPG is a Hack. There is no established law for this distinct game. Not yet. Not until the GM makes their judgment.

Now, one of the problems with OSR and FKR play — if you can call it a problem — is that judgment is, by definition, subjective. It require a lot of trust at the table. Rulings can be arbitrary or poorly reasoned, and if a judge feels one way while the other players feel another, that can create friction that will have to be dealt with.

If a player explains how they’re checking for traps or persuading a guard, the GM might judge their description unsuitable to find this particular trap or seduce this particular soldier. Then the trap is sprung and the player complains because of course they were using the ten-foot-pole, they hadn’t needed to explain that to their usual GM for over twenty sessions, now. They’d have known what they meant.

Some would say it’s better to have pre-established rules, the “higher power” of the rulebook, to avoid complaints and maintain expectations. It keeps things fair.

Fair?

We were all kids once, our vocabulary was smaller and our understanding of complex concepts limited, but what on earth did we mean when we said an everything-proof-shield wasn’t fair? What does fair look like in the confines of imagination? When we’re making up a story — a story that can be about anything, where people can do anything — what does “fairness” even mean?

War isn’t fair. People aren’t fair. Stories aren’t fair.

Playing pretend is a largely lawless affair, and as we grow older we may find ourselves wanting more structure in our play. Some prefer the rules of dice and numbers, math and probability. Our character’s stats are clearly written down and we can all see the number on my die. What happens, happens, and that’s all there is to it.

Others embrace the structure of narrative. There is a case to be made that I have been a little unkind to Wargaming; by dividing the parts of RPGs into Story and Game, Books and Wargames, I imply that Wargames do not have game-narratives of their own. Allen Ward makes the case that table-top wargaming is successful because of its overarching stories. Moving pieces around on a board and rolling dice is no more than an overly complicated chess game; gripping in its own right but largely passionless without the structuring narrative behind it. One becomes more invested and engaged in their army pushing forward to cleanse a planet of alien heresy, rather than merely testing your tactical acumen against your friend.

One could argue that tactical wargaming has just as much game-narrative as any RPG. What we think of as strategy and tactics could actually be suggestions of how the story of the battle should unfold, as improvisational as any meeting in a tavern, as much game-narrative as anything else.

Is “I order my archers to focus fire on the army’s left flank” any more or less of a tactic than “I offer the guard a few coins to let us pass?” And if we’re fine with our GM making judgments about the latter’s success, why not do the same with the former?