Lady Blackbird, and Railroads

Lady Blackbird is, in fact, Chapter one of Tales from the Wild Blue Yonder, three pre-built one-shot adventure modules where you play as pre-made characters, in medias res, with a carefully constructed scenario for you to play through in an attempt to fulfill your character’s goals.

It’s not as locked-down as that makes it sound. For all the pre-building these characters have gone through, there is a lot of flexibility in how the characters are played and how their backstories are revealed. You spend dice to do certain actions, and you can regain those dice by inventing and revealing bits of your backstory to other characters. You get bonus dice or XP whenever you do something that connects with your characters motivations, but its up to you how they connect. You can also buy off certain motivations and replace them with others if — in narrative — your character changes their mind.

But you can’t create your own character. You can’t start anywhere but locked in The Owl’s brig. If you’re Lady Blackbird, you are on the run from your arranged marriage, no ifs, ands, or buts.

Isn’t that a bit railroaded?

Maybe, it depends; railroading is another one of those terms, that everyone knows the definition of, but don’t all agree.

Some people see railroading as purely a narrative flaw, when the GM has fallen in love with a pre-built story so much that they don’t allow for player agency.

Some say that railroading itself isn’t what’s bad, it’s when players can tell they’re being railroaded. It’s the proverbial “seeing the strings” that breaks the illusion.

Others see any GM construction at all as railroading: if there’s a fire in the diner, and the windows are locked, and the front door is swarmed by zombies, then you’ve railroaded the party into going out the back door, and that’s bad.

We can see right away that isn’t a great definition; it could also apply to things like die rolls and established world-building. Rolling dice isn’t railroading a player, anymore than not letting them play a magic-user in a hard sci-fi adventure; and if a sudden shadow overhead precedes a surprise burst of dragon-fire on your head, that’s not “railroading you” into fighting a dragon.

And that’s not as banal a sentiment as it may seem: some railroading is required in gaming. If the game is about killing a tyrannical dragon, and the players don’t want to go fight the dragon, then maybe that’s not railroading; maybe the players just don’t want to play the game.

It can’t be railroading to help a party focus on a goal, can it? If a group of characters enters a hotel hallway and hears shouts for help from the door at the far end, is it really railroading to say that all the other doors are locked and can’t be broken down, so don’t waste your time? Or is that just encouraging the players into more realistically heroic behavior?

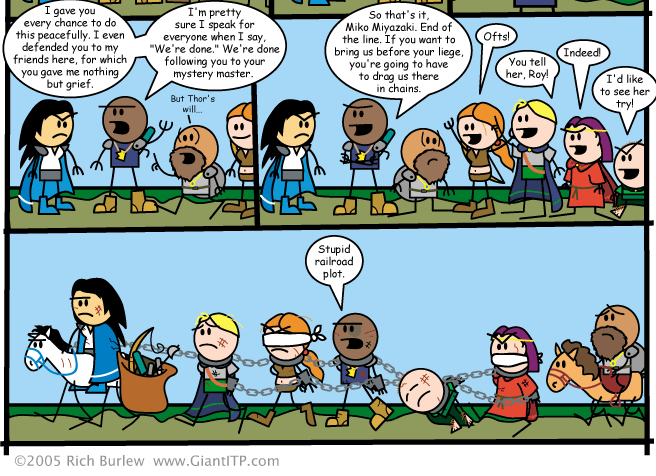

To put more evidence into the “see-the-strings” column, when we think of bad railroading, we usually think of a clumsy GM’s attempt to control the narrative: You want to kill the villain’s henchman? Too bad, he escapes, because he needs to be alive to capture the princess later. You want to head to Secondtown before going to Firstville? No, your carriage-driver misheard you, because you need to meet the exiled rogue bandit in the Firstville tavern before reaching his old turf. Want to turn right? You can’t. You somehow managed to take the left fork instead!

We can look at “railroading” as not a distinct problem, exactly, but rather a symptom of a larger problem — or at least a larger question. Consider the following scene in an RPG: A fight has broken out in The Bar. The Kid swings their foot towards the closest groin. The Face pleads for calm. The Brute thinks for a moment, and then asks the GM, “Is there a chair nearby?”

Is there a chair nearby?

I would like for you to think, for just a moment, about a bar. Every bar you’ve ever been in. All the bars you’ve never been in. Is there a place you could stand in a bar that didn’t have a chair nearby?

We’ve all heard this, we’ve all said this at least once. We find ourselves in a situation, we try to decide what to do, and an idea begins to blossom. We think a bit more and then ask the GM a simple question for more information. We ask the GM to clarify something about the world they created.

We ask to be railroaded.

“Is there a chandelier I can swing from?” “Are there handholds in the wall?” “Can I open the door?” Why is it that we feel the instinct to ask obvious questions whose answers can only hinder us?

True, a lot of this is just grammar. There is functionally little practical difference between “can I open the door?” and “I try the handle to see if its locked,” but the difference is there. It lies in the percieved role of the GM; specifically, it is the GM who dictates the world, and no one else.

This is the natural result of what I called Rule Zero; the idea that the GM is “the person in charge.” What they say goes, and the other players can’t do anything about it. To say “I grab a nearby chair” when the chairs have not been established by the GM is akin to a powergrab, establishing something in the world when such powers are reserved for the GM. Even FATE magnanimously demands a fate-point for the privilege.

If there is a parallel to be drawn, it is with computer adventure games of the 90s. Point-and-clickers from the game studios of LucasArts and Sierra evolved into Myst and The 7th Guest along with a million escape-room flash games, all built around a single unavoidable design choice: a puzzle has one correct answer.

It’s inescapable for digital media. Roger Wilco is trapped in his cell, and the only way out is to manufacture a decoy out of his food rations. Laverne is trapped in her cell, and the only way out is for Hoagie to change the American flag into a tentacle-suit. Indy has to “look at” the wine bottle before the slimy guy will let him take it. Guybrush has to pull down the pirate flag to put in his potion.

Railroading is a symptom of a conflict between two specific kinds of play: the ones where you discover the way forward, and the ones where you create the way forward.

And let me state here and now, one is not better than the other. I think it’s too easy to be down on point-and-click style adventure games these days. Especially Sierra games; those buggers would kill you for looking under a rock, but there was nothing wrong with that because the point of the game was to learn the correct order of actions that would get you to the ending screen, like an overly gussied-up GROW puzzle.

Ian Danskin of Innuendo Studios describes computer adventure games in his Who Shot Guybrush Threepwood series first as “Puzzles and Plots,” then later adjusting the definition to “Puzzles as Plots.” I will not reiterate all three videos here. Go watch them. They’re great, and that definition fits with Tabletop RPGs pretty well. What is a puzzle, but a mechanic? What is a plot but a story?

The major difference is there are more “right answers” to an RPG puzzle. Getting past the guard may need a persuade roll, a sleep spell, a stealth check, a knock-out hit, or a carefully thrown rock into the bushes. Even the best adventure games rarely had multiple solutions to a puzzle, but with RPGs there are as many solutions as the GM allows.

And that’s the kicker right there; unlike a computer, the GM decides if the offered solution is correct, and perhaps more importantly, can be persuaded.

Players want agency over their characters and their stories. Not complete freedom — we are usually willing to be bound by narrative tropes and conventions — but if our character does something, we want it to matter. We want our actions to change the game. So what happens when player choice and agency runs headlong into the plot? What if the players miss something important? If they were supposed to find the journal in the victim’s hotel room, what happens if they decide to get on the bus to Atlantic City before finding it?

A good GM won’t let that happen, and that requires some measure of railroading.

Doesn’t it? What would it look like if it didn’t? What is the antithesis to railroading?

Next time, we’ll talk about sandboxes.