QZ, and Sandboxes

Inspired by Annihilation and Roadside Panic, QZ is about the Quarantine Zone; a place where the laws of nature decided to take a holiday and turn the area into a surreal fever dream. The game itself is not a horror game, nor comedy, nor drama; but the QZ can be horrific, funny, and dramatic in turn.

In the instructions on how to use the rulebook, the book clearly states that the game was designed to be played as a sandbox.

What does that mean?

QZ doesn’t have an overarching plot. There are no established modules, no metaplots of powerful figures who are doing all the cool stuff while you fumble around gaining levels by squishing goblins. There are no narrative hooks beyond the established world: There’s the QZ, here’s your environmental suit; go explore and, if you’re lucky, survive.

This isn’t to say there aren’t quests of a sort. The game explains how to handle “side quests” established through your character’s contacts and backstories, but the QZ isn’t a Foozle to kill. It’s not a McGuffin to possess or control. The QZ is a place where things happen.

Sandboxing is the antithesis of railroading. Sandboxes have no overarching goals, structures, or guardrails. Instead, you are dropped in the middle of a world of people, towns, dangers, who knows what else, and it is entirely your own decision in what to do. You find strange beasts in the QZ; do you want to capture them for study? Eradicate them? Talk to them? It’s entirely up to you!

In a larger sandbox, the number of options increase. Do you want to go to the next town over? Great! Find bandits on the way and want to send them scattering? That’s fine. Or maybe you want to take over and become their leader. Perhaps you ignore them because you want to look for technology of the ancients, so you scour libraries for locations of long-lost catacombs. Maybe you want a title so you decide to join the intergalactic military to further your political career. Maybe you just pick a direction and start wandering.

This kind of freeplay can be incredibly rewarding when done well. Minecraft hasn’t become so famous because of a great storyline. If you want to play a game where you discover an ancient ruin, you can go look for one without concern for any tyrant kings or evil dragons who are sitting, tapping their feet, waiting for you to show up.

The obvious question to ask, then, is: does this mean that sandboxes can’t have plots?

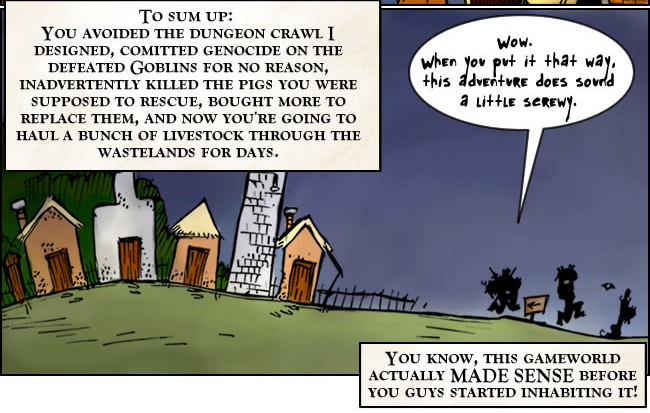

If you clean out a tomb and kill a lich…so what? When you leave the tomb, will anything be different? Is there anything happening in a sandbox that you don’t put there? Consider the limitations of sandbox video games and how sterile they all are. No matter what you do in the game, it always returns to the status quo. Even if there are things to do, they rarely change the world in a meaningful way.

At the same time, that kind of freedom can be paralyzing. After all, you can’t do anything. If your character assaults someone in an alleyway, the police better come after you or else you’re not playing in a world but in a painting. If you overthrow a monarch and take their throne, can you just walk away tomorrow and become a wandering minstrel? If you can, then what does anything you do actually matter? If you can’t, then are you really in a sandbox?

And that’s just focusing on in-game practicalities. What about preparation? If you spend a day seeing the sights in a city, meeting all the NPCs and learning all their names and backstories, is it fair to skip off to the next kingdom the next day? Is the GM really supposed to spend all their time making another city’s worth of NPCs just for you to gawk at for a bit before heading somewhere else?

Sandboxing as an idea is complex, primarily because the line between freedom and significance is difficult to walk. Balancing both choices and consequences is hard to do, and it’s made much easier in a smaller space: fenced in with plot and narrative. NPCs can be made richer and more interesting if the GM knows you’ll be spending time with them. Foreshadowing, plot hints, puzzles, all number of obstacles can be put in your path, so long as you have a path the GM knows you’ll have to walk at some point.

Obviously, the goal is an ideal blend. You don’t want a game that’s more or less a sight-seeing ride, moving from carefully constructed plot-point to plot-point, going through the motions and saying the expected lines; you want a game where you have the actual freedom to do as you see fit.

At the same time, you don’t want a game without structure, narrative significance, and meaning. You want a rich and vibrant world that doesn’t have paper-thin cliche NPCs that are little more than window dressing, and a story where you actually have a purpose.

So we have sandboxing, which favors player freedom; and railroading, which favors narrative structure. Can we blend the two? Of course we can, though there are lots of differing opinions about how.

Playing-the-oval is one, where you railroad both the opening and closing of the plot to both set the players on the right path and ensure the Foozle is vanquished or the McGuffin found; and let the middle be more sandbox, with the freedom for the players to explore the world, find allies and resources, and decide how they want to get to the final castle.

There’s railroading the opening of the game and then cutting the players loose afterwards. There’s letting the players do whatever they want, but keeping an omnipresent evil always in the distance, letting the players decide when to go to the railroaded ending with all their collected loot and experience. You could railroad your quests and force players to solve specific puzzles, while sandboxing your world to let them go where they want and find quests as they like; or you could railroad the world as NPC factions and external forces drive the larger metaplot, while each quest is a sandbox, with players deciding how or if they will progress through each one. There’s also any number of alchemical mixes in-between.

Going whole hog into sandbox or railroad is also acceptable, as long as the players want that kind of game, and the GM is willing to run it for them; But that’s a little unsatisfying of an ending for me. Sandboxing and railroading aren’t just different techniques or tools for a GM to play with, they are also parts of a greater whole. After all, the whole point of this series is to detail how RPGs are a medium, not a genre.

So let’s look at a couple games that turn sandboxing and railroading into fundamental aspects of their gameplay. Let’s jump off the two opposing edges of this spectrum, and see what lies beyond.