Starlight Riders, and Story Structure

Starlight Riders is a card-driven heist-focused space-western with a 50s cartoon aesthetic. According to the website, “You play as a bunch of outlaws, fighting against an oppressive system that took all you had. It’s your role to tip the scales back in favor of the forgotten.”

GM-less and designed for one-shots, Starlight Riders is great for low/no prep games. There are a lot of little interesting quirks with the system: players get a few cards instead of a distinct “character sheet,” and as a troupe RPG, any player can play any character at the table. Gameplay alternates between cards, dice, and roleplay fairly smoothly along the game’s three-act-structure.

That last sentence should raise some eyebrows, no? It certainly did mine. Generally, RPGs ignore the literary concept of story-structure, relying on the chaotic mess that is improvisation to structure the story organically, if at all. I mean, the case could be made that RPGs can’t have story-structure; what if the players want to do something different halfway through the story?

If we want to know how to tell a good story in an RPG, we have to at least ask if we know how to tell a good story at all.

It’s hard to categorize what makes a good or bad RPG story. Stories are ephemeral and subjective enough that at best we can say: if the players like the story being told, then it’s a good story. Philosophers and artists have spend generations trying to define good stories, and I don’t think I have the ability — much less inclination — to try and join them on their quest.

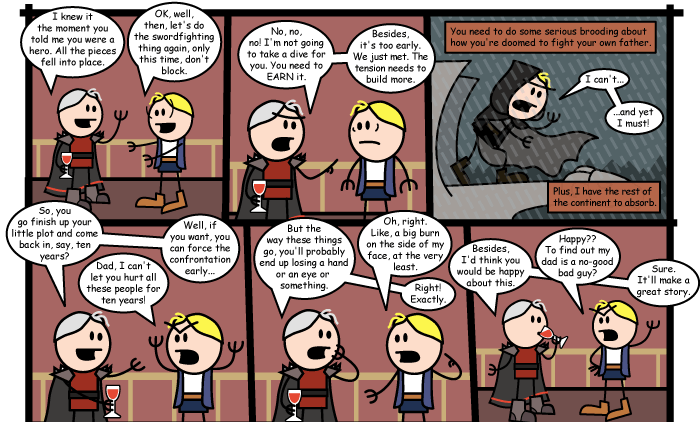

But we can consider the difficulties. At the beginning of an RPG, for example, the players don’t even know what the story is. A lot of narrative structure is dependent on the writer knowing where the story is headed, so how can you improvise things like foreshadowing? When would be the best time for a revelation about a character’s secret past? What about building romantic tension? What about rescuing the humble ally who will provide your characters with a vital piece of information in Act 3? Which of the thousands of guns laid out in front of you throughout the game happen to be Chekhov’s?

At the same time, by virtue of being protagonists, the majority of the story is decided by the players’ actions; do you let the tyrant live to stand trial, or enact your own brand of justice? Do you talk to the Dragon about its behavior, or do you just kill it? Do you turn left or turn right?

There is a school of thought that suggests telling a story is less about the content than it is about the structure. Literature scholars and post-modernists love to talk about monomyths and universal stories while codifying arcs, climaxes, pinch-points, and more until writing feels less like a creative endeavor and more like painting-by-numbers.

That’s a hyperbolic way of putting it, but the point stands. Whether the Three Act Structure, the Seven-Point Structure, Freytag’s Pyramid, The Hero’s Journey, or Dan Harmon’s Story Circle, there are people who think that the content of a story must be organized. Whether this is a universal truth about storytelling can be argued, but we can certainly agree that these story structures are at least, nowadays, familiar, if not expected.

Could we say the same of game- and meta-narratives — that one is only there at the largess of the other? Personally, as always, I think both views have their merits.

Starlight Riders experiments with the idea that structure is at least as important as agency. It embraces its one-shot nature to lean into the three act structure; the game isn’t about sprawling landscapes and the disjointed chaos of a person’s life, it’s about the exciting things that happened during this specific heist. It’s about a space-train robbery, a zap-gun shootout, or a galactic poker game.

How does it work? Starlight Riders gives players “moment” cards, either chosen or picked at random. The players organize these moments on the table into one of three separate acts, designated the Preparation, the Execution, and the Extraction. Each moment is something the characters are trying to get, trying to get to, or trying to get through. They’re plot beats, in essence.

Once the structure is built the players then get a number of “snag” and “twist” cards. Snags are hitches in the plan, like temptations, faulty gear, or sudden snake pits. Twists are larger narrative shifts, such as the whole heist being a setup, the prize not being where they thought it was, or sudden Space Ninjas.

The game then goes through each moment with each player rolling dice to see how their characters perform. If they roll well the story progresses. If they roll poorly they take “heat” and may eventually get into “hot water.” This means they can’t continue until a “danger phase” is passed, with involves drawing a random snag or twist and placing it on an incomplete moment card: things get narratively dicier if the players roll poorly.

And its not just with snag cards; making personal sacrifices for the team or having backstory-revealing flashbacks are all given mechanical weight in the game. Ludo-narratively, Starlight Raiders plays with the idea that character action and narrative structure are inexorably linked.

Generally, RPGs try to keep players focused in their own lanes. Players decide what their characters “do,” and that’s it. It’s the other players’ job to react and adapt, causing the narrative to evolve naturally. If there are climaxes, low-points, or rising actions, they are accidental and perhaps incidental to the game itself.

Starlight Riders rejects this idea, calling out the kayfabe and telling players that the story is their responsibility. They aren’t just deciding whether their outlaw fires their gun or jumps to the side, they’re deciding whether this moment is narratively significant or not.

Gamifying this, giving the players control over the high and low points in narrative structure, is a fascinating design choice. It forces the players to look beyond their exclusive duty to portray their characters in the game, and recognize that each character also has a duty to the plot.

And lest I suggest the game is unique in this, the RISE SRD — used in games like Rise of the Apes or Therefore iAm — also taps the 3-act structure for inspiration. Less geared towards long-term play, the RISE system gradually introduces attributes, skills, and abilities over a one-shot adventure. It’s more concerned with character creation and growth during the story than the plot-beats of the story itself.

If you prefer Starlight Riders’s model, you could certainly hack the system to play another kind of story; all RPGs are hacks, so there’s nothing stopping you. That said, we can easily see how Starlight Riders’s type of play is easily supported by the system’s established framing, right? I mean, surprise Space Ninjas are great for space-western heists, but not for gritty fantasy. The rich and untamed aesthetic of Starlight Riders is just dripping from the game. You can feel your star-spurs clicking with every move. The system is ludo-narratively tied to playing a space-western.

In a world where Starlight Riders becomes an SRD like RISE, I can imagine a version for every kind of fantastical story: One for climactic fantasy swashbuckling, one for dark paranormal thrillers, one for hard-sci-fi survival stories, horror slashers, period romances…

But this brings us to another interesting question about telling stories; about culture in general, in fact. Where do our stories come from? See, if you wanted to hack the Starlight Riders model, you have to start with “hack into which genre?” A Starlight Riders SRD isn’t suited for a universal system or improvised narratives; it’s for telling stories “in-the-mold-of.”

It’s been said that “we tell the stories we’ve been told.” What does that mean for RPGs?

Next time, we’ll talk about media-influence on RPGs.