I Got Hit By A Meteor & Was Reincarnated as the Hero of a Tabletop RPG, and Fiat

I Got Hit By A Meteor & Was Reincarnated as the Hero of a Tabletop RPG is an RPG and I am not typing all that out again. I’ma call it Meteor.

Meteor is purportedly a redesign of D&D 5th edition rules, with the framework detailed in the title; the players are dead, having been crushed by a meteor, and the devil has offered to redeem the players’ souls if they beat him in a game of 5th edition D&D.

I say purportedly, because that is not what this game is about at all.

What Meteor is actually about is embracing a deconstructionist absurdity about roleplaying in general. It’s about saying “Ah yes, I remember the Chainsawer sub-class from Tasha’s Cauldron of Everything. You deal 2d20 damage per swing.” It’s about saying “That potion gives you +5 to hit, which means you add 5 to your damage.” It’s about saying “Nuclear Punch is a level 9 spell, so you can only cast it six times before you have to erase it off your character sheet.” It’s about saying “You find your first King’s Coin, so now the player shop is unlocked and you can purchase cosmetics.” It’s about damage types like “Fire, Ice, Holy, Fish, 4k 60fps, and Classic Rock.”

You know, the standard D&D 5th edition ruleset.

You play the game like this, pulling rules out of your fevered imaginings and boosting your personas to absurd levels as best you can, until such time that the GM struggles to resolve a conflict between multiple established rules, or a chain of wishes stretches on into infinity, or the amount of gold the characters are carrying is too much for one meat-computer to handle. When the players break the game, the game ends.

Meteor is, in no uncertain terms, an absurdist deconstruction of roleplaying in general. It’s looking at one of the fundamental aspects of RPGs — remembering the rules — and pushes that behavior to the extremes. It is about crashing the game.

It’s an interesting ludo-narrative, a game who wants you to fall apart at the end, laughing at its own absurdity. It’s playing patty-cake faster and faster until you just give up, your brain and body failing to keep up with each other until you collapse into giggles, drunk on the feeling of zen nonsense.

And it wants you to get there by carefully and purposefully mocking the rules of roleplaying.

When I talked earlier about hacks I made the case that RPGs could be considered nothing but hacks, each as unique and individual as the players who play them. But what about rules for specific situations? What if the players don’t care enough to even make a rule?

There comes a point in every game where the GM waves their hands. Like a wizard, they gesture aimlessly in the air, and a whole subset of rules is wiped clean from the world. The GM decides on a whim that the game would not be served by opening the rulebook one more time, delaying the game’s pace to work out what dice need to be rolled.

This is GM Fiat; Rule Zero, in some circles. The GM is the final arbiter, and what they say, goes. They are unto a God, and if they say that rocks fall and everyone dies, you have no power to dispute it. Even the most rule-heavy predictable formulaic ruleset can fall to fiat gaming at the GM’s judgment.

Is this a bad thing? Or just unavoidable?

Players enter a game with a single expectation; “I bind myself to the rules of the game, in the belief that everyone else is likewise bound.” This oftentimes applies to the GM as well; but the GM never has the same rules. The GM, as arbiter of the game, says “what happens.”

Yet every GM has had the experience where a player is about to die, and they enact mercy on the poor soul. “Oops,” they say, quickly picking up their die from behind the screen, “the dragon missed. Wow, that was unlucky for me. Okay, your turn, cleric. Do you want to heal your comrade?”

It can happen in a myriad of little ways. Perhaps the GM decides that the trap they set was not really there. Maybe the Merchant wasn’t as crotchety as first envisioned. Perhaps the forcefield could only be opened with a keycard, but their solution was so innovative it just had to work.

Or this combative GM doesn’t like how easily this big-bad is going down. A sudden arrival of reinforcements that weren’t there before, an earlier ruse was miraculously planned for, or even a lucky guess from a PC resulting in a hastily re-written trap.

This behavior stems from the idea that the rules exist only to provide a modicum of structure to the storytelling. An adventure is unsatisfying if the dragon eats the princess at the last hurdle, so we ignore the dice if they say that’s what happens. Rules are bent, dice are fudged, the game is subverted not just for the game-narrative, but the meta-narrative as well. Enjoyment is put over the demands of the system. This is exemplified by one of my friends’ semi-regular exclamation, “Well, you made your roll versus awesome, so it works.”

This turns the GM into a tinkerer; a hacker of hacks whose only goal is to maintain the players’ sense of fun, while hiding their moves behind the curtain.

Rules are not fun.

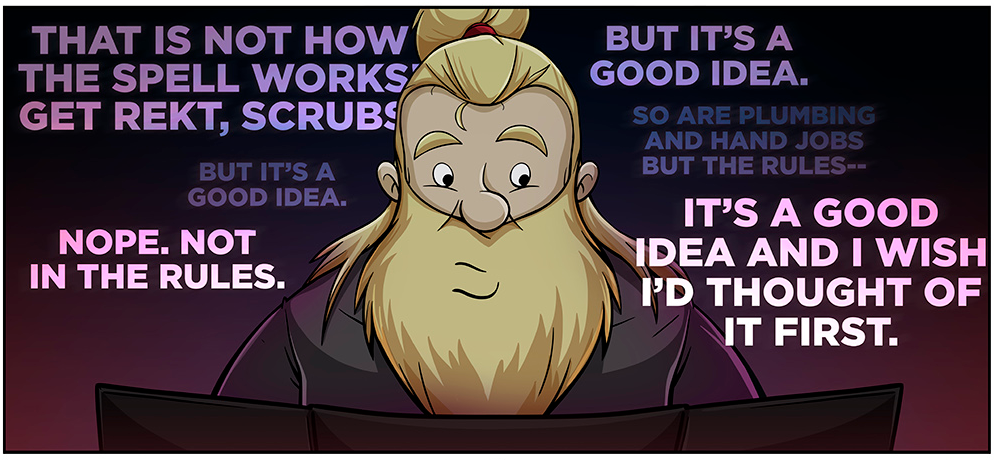

Figure 1: The Angel and Devil on all GMs’ shoulders.

Fun can come from the rules, certainly. Walking is no great challenge, but walking across a balance beam can be. Rolling dice is meaningless without rules to explain which rolls are successes and which are not. The fun comes from reacting to the rules, finding our path through the game while bouncing off proscribed behaviors. Perhaps you can only touch the ball with your feet. Perhaps only with your hands. Perhaps letting go of the ball is called fumbling, or perhaps its dribbling. Moving from room to room in your house is boring unless “the floor is lava.”

Roleplaying Games are perhaps unique in that there is a singular arbiter of the game who is both distinct from and a part of the game. The GM is a referee or umpire, calling balls and strikes and passing judgment on the rules, but they are also players. Their duty is not solely to the rules, but the game experience as a whole. It is their job to make sure that the rules do not keep the players from progressing, the story from unfolding, the game from being fun.

A lot of systems these days build hand-waving into their systems, saying if a rule doesn’t make sense, or hinders the flow of play, or just isn’t fun, then ignore it. This is primarily a tool designed to keep the rules of the system subservient to the players. It’s your game, not the rule-book’s, not Wizards of the Coast’s, and if a rule causes consternation then you’re better off playing without it.

For some people, this is cilantro; perfectly fine in small doses, but overpowering when used too much.

Because if rules can be tossed aside for the sake of the fun, why have them at all? If the chances of hitting a demon with your sword are 60% normally, but 100% if you make up a cool-sounding move, then isn’t that just a little unfair?

Rules certainly aren’t automatically fair, but they are impartial; and if we all agree to abide by the rules, then everyone can have a good time, right?

Meteor laughs at the whole conceit from beginning to end. It’s nonsense. It’s Calvinball. It’s pulling out everything-proof-shields and then countering them with everything-proof-shield-piercing-swords. It’s infinity +1. It’s everything a hardcore rules-lawyer is terrified of; a complete lack of systemic structure beyond your own mad imagination.

Meteor reminds us that rules are there because we want them there. We are ultimately the ones with the power to change the rules as we see fit, and rules are only as useful or binding as we allow them to be.

Now that leads to a very interesting question…are some rules just better than others?

Obviously fun is subjective, but we can see how some rules survive and spread through the RPG ecosystem, while others fall into obscurity. I don’t think anyone is planning on mining The World of Synnibarr for rule ideas, for example.

At the same time, I don’t think we should mistake familiarity for quality. “A bird in the hand,” after all, and when a whole new RPG enters the market, asking players to learn a new ruleset in addition to a whole new world-setting can be a significant barrier to entry.

So what happens when a set of rules is either beloved or ubiquitous enough to last between games? Next time, I’d like to address Scions.