FATE, and Ludo-Narrative

I described FATE as a system earlier; but my description was a poor one, abbreviated to get to the point I wanted to make. The actual rules of FATE are more detailed and interesting than I perhaps first made them sound.

Characters in FATE Core have two fundamental things that influence their abilities: aspects, and skills. Skills are simple enough; they’re what your character is good at and have a numerical value from 0 to +5, usually. Aspects are simple sentences that apply to your character. “The best star-pilot in the galaxy” is an aspect, for example. Or perhaps “Never gonna take no guff from nobody.” They can be quotes, phrases, explanations, descriptions; anything the player and GM agree describes the character narratively, rather than numerically.

This raises some interesting questions. After all, in D&D we know that a character with strength 18 is stronger than a character with strength 12, but what about the bouncer who is “built like a brick wall?” Are they stronger than the “Rough and tough cowpoke from the sticks?”

Well, that’s not what aspects are for, exactly. Let’s say your character is in a bar, someone tries to start a fight, and you decide your character wants to intimidate them into backing down. You’d roll your dice, add your “intimidate” skill level to the dice total, and then decide that because your character is “never gonna take no guff from nobody,” you can add a +2 bonus to the roll. It’s always +2, so since someone “built like a brick wall” adds the same bonus as a “Rough and tough cowpoke from the sticks,” we could say they are equally good in a fight, to the extent that we’re just focusing on physical strength.

But fights aren’t just about physical strength, at least not narratively. A bouncer who’s built like a brick wall might take repeated hits to the stomach without flinching, while the cowpoke might win the fight by grappling the big bull-like bouncer from behind while shouting “get along little doggie!” Conflicts in FATE aren’t solved by comparing numbers, they’re solved by comparing stories.

That’s pretty ephemeral, isn’t it? I mean, who’s to say that “never take no guff” applies to any given situation? What’s to stop you from just steamrolling the narrative with character successes that don’t come from explanations, but excuses?

This is the problem of the “everything-proof shield.” Narratives thrive on struggle and conflict, and if someone is given the goal to win with their imagination, then where is the challenge? I can just say my warrior is even stronger, my wizard even smarter, or my zap-gun re-calibrated to pierce the impenetrable shield.

In FATE, this is managed through the Fate Point system. Being able to get that +2 bonus from your Aspects requires “fate points,” a limited resource distributed at the beginning of the game. To get more FP, your character has to let their aspects cause trouble. Perhaps because you “never take no guff,” you mouth off to a cop and land in jail. Perhaps because you’re the “best star-pilot in the galaxy,” you underestimate an opponent during a race, or overestimate your ability to navigate an asteroid field. Being a “rough and tough cowpoke” might mean you make embarrassing social mistakes in polite company. In each of those situations, your character is in more trouble than they would be otherwise, and you get a fate point.

The key is; for FATE to work, both the GM and the Players have to work at ensuring a steady ebb and flow of fate points, which naturally creates an ebb and flow of narrative. This combination of mechanical rules that encourages a certain kind of play composes FATE’s effective ludo-narrative.

This is the third kind of narrative that all RPGs have. Ludo-narrative is a concept established primarily in video game design, that I am slightly re-purposing here. If game-narrative is the story of the imagined fiction, and meta-narrative is the story of real-life, then ludo-narrative is the story of the game system in being played.

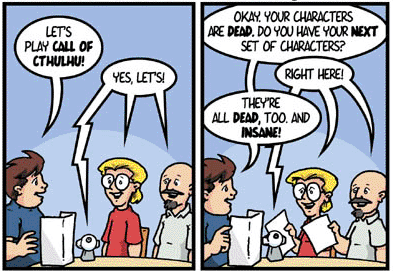

Figure 1: This joke wouldn’t make sense without ludo-narrative.

Let’s look at an example: the original Dungeons & Dragons had extensive rules on how combat worked, detailing magic spells and armor classes and hit points and charts upon tables upon charts. However, if your magic-user got into an argument with a noble, or wanted to haggle for a cheaper price for a dagger, there were no rules for that. What happened was up to you and your GM, not the system itself.

This leads to an interesting question: Is your character getting into an argument with a noble part of the game?

I mean, it’s not in the rules, is it? Nor is haggling; the rules just list items and their price. The original rules of Dungeons & Dragons was focused entirely on dungeon delving, monster slaying, and gold taking. If you roleplayed outside those confines, were you even playing Dungeons & Dragons anymore?

This uncertainty shapes the ludo-narrative of D&D: combat and exploring, not plots and politics nor arguing over prices. Dragon Warriors, an old RPG from the mid 80s, didn’t have any rules for stealth or perception until the fourth book, because players weren’t supposed to sneak around, they were supposed to fight. Lay On Hands has no bespoke combat rules at all, because the game isn’t about fighting.

Every system was created to tell a certain kind of story. This is different than a game’s setting: a game can purport to be about adventurers slaying dragons and rescuing royal progeny, but ludo-narrative is independent of a game’s setting. The ludo-narrative is story that the system itself tries to tell.

Call of Cthulhu is a horror RPG based in the works of H.P. Lovecraft. Characters are of middling ability, and are not expected to live long or remain sane through an extended campaign. Mechanically, character growth is limited and progressing through the game is as dangerous as remaining ignorant of the terrors that stalk you. Call of Cthulhu is a game about being afraid, disempowerment, and Pyrrhic victories.

Lancer is a game about mech-pilots fighting other mechs. Abilities are complex, with detailed mechanics involving placement, conditions, and status effects for both allies and enemies. No one character can be good at everything and everything is needed to succeed, because Lancer is about combat, strategy, and tactical teamwork.

Dread is a horror game played with a Jenga tower. When your character takes challenging actions, you pull one or more blocks from the tower. If the tower topples, your character dies. The tension of the wobbling tower perfectly mirrors your character’s tentative footsteps down the darkened hallway. The growing tension of “when will the tower fall” and “when will the killer strike” are played in harmony, because Dread is a game about the building of suspense.

A Good Death is a solo-game about a hopeless situation, where you either accept or contest each twist of fate that comes your way, choosing whether and when to spend your limited resources. You then write about what happened, detailing the events you have lived through, until your final death. What is A Good Death about? As the game says: “There is no winning. There is no victory. Only certain death. You only get to choose how you meet your fate.”

And then there’s FATE, which is designed for “proactive, capable people who lead dramatic lives.” While technically a Universal system, the game itself geared towards pulp settings, with a “give and take” flow of storytelling that sees the characters reach dramatic highs and lows, because FATE is a game about exciting adventures; Adventures told by the GM, the Players, and the game itself.

FATE’s ludo-narrative supports this: at tense moments in the game-narrative, with your character facing down their long-time rival, you sit there facing your GM, deciding whether or not their bargain of a fate point for failure is a good one to take — a tense moment in the meta-narrative. The ludo-narrative of FATE’s system encourages these moments: do you have enough fate points to claim a success now? Or do you wait for a bigger payoff later? Can your character survive their personal flaws causing trouble at the wrong moment? Or do you keep things safe now, at the cost of help when you may need it most?

Sweat drips off your character’s nose as they finger their sword-hilt. You finger your dice as you wipe your brow…

Now, a strong connection between game-, meta-, and ludo-narratives is not requisite for a good RPG, but more and more systems are starting to recognize the power that a solid ludo-narrative can have on the stories a system tells.