Dungeons & Dragons, and Defining our Terms

Dungeons & Dragons, as you may know, is an RPG.

No, that’s doing it a disservice. D&D is the RPG.

Arguably the first of its kind, D&D certainly became the definitive example of the medium. It has dominated the cultural dialogue about RPGs to the point that even if you know nothing about RPGs, you’ve still heard of Dungeons & Dragons. It’s difficult to explain how ubiquitous D&D is as a concept, not just a game in and of itself: It has spawned books, clones, parodies, movies, and even a children’s cartoon show, although we can probably blame that last one on the ethos of the 80s more than any inherent merit.

Terry Pratchett once said of J. R. R. Tolkien: “[He] has become a sort of mountain, appearing in all subsequent fantasy in the way that Mt. Fuji appears so often in Japanese prints. Sometimes it’s big and up close. Sometimes it’s a shape on the horizon. Sometimes it’s not there at all, which means that the artist either has made a deliberate decision against the mountain, which is interesting in itself, or is in fact standing on Mt. Fuji.” I think the same applies here.

I could go into the game’s history in great detail, but time is a finite resource for us all, so I’ll paraphrase. D&D was built on the backbone of Chainmail, a medieval tabletop strategy game similar to Warhammer, Malifaux, or Star Wars: Legion. As the rules evolved, the game began to include heroes, elves, dragons, and similar Tolkien staples. Eventually the rules expressly suggested playing battles based on Tolkien’s work, as well as other fantasy authors. This evolution resulted in the first edition of Dungeons & Dragons, an RPG birthed from a synthesis of tabletop wargaming and fantasy novels.

Now, I have my own issues with the concept of “genre” as a method of classification. It is fairly clear that what influences a genre is association with the historical era and recent inspirations, making “Tolkien-like,” “Rice-like,” or “Heinlein-like” far more effective designations than “Fantasy,” “Sci-fi,” or “Romance.”

At the same time, we could call D&D a “Chainmail-like,” Chainmail a “Siege of Bodenburg-like,” and keep going backwards until we get to calling Hellwig’s wargame a “chess-like;” and that’s without acknowledging that kids playing with dolls/action-figures must have some familial connection to modern RPGs.

Besides, there were a lot of roleplaying games that came out in the late-70s early-80s, including Runequest, Traveler, Gamma World, Superhero: 2044, Rolemaster, Call of Cthulhu, Paranoia, and Mechanoids. Tunnels and Trolls came out only one year after the first printing of D&D, and Empire of the Petal Throne was the first ever published game-setting.

So to say that D&D created a new genre of game is perhaps inaccurate, and certainly reductive. What we can say is that D&D invaded the social consciousness in a way that no other RPG did.

As has been said by others, for better or for worse D&D’s notoriety has made it “the entry point” for RPGs. If you know nothing about RPGs, you know about D&D, which makes it the first place anyone will look if they want to learn about RPGs.

So are all RPGs “D&D-likes?” Years ago, that moniker might have fit better than it does today. Call Troika!, for example, “like D&D,” and anyone familiar with both will wince a little. There are parallels to be drawn, certainly, but saying if you like D&D you’ll like Troika! is…a risky recommendation at least.

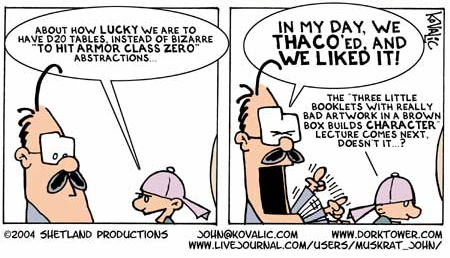

Even D&D itself, for all its posturing at the beginning of the 5th edition Player’s Handbook about the game’s origins and being the “best of its breed,” is almost nothing like the first edition D&D ruleset. With the changes between 1st and 5th edition, you could make the case that there are many other modern games more “D&D-like” than D&D itself.

Figure 1: A lot has changed since the 70s, you know. A lot.

So I think it’s a mistake to cling too tightly to D&D as some foundational aspect of Roleplaying beyond its historical significance. Understanding the evolution of RPGs and how we got here does not change where we are.

So, if we’re going to look at RPGs as a medium we need to have some kind of working definition. What actually is a Roleplaying Game?

The only answer — at least, the only accurate answer to any “what is” question — is “that which we point to when we say ’that is an RPG.'”

Wittgenstein had some right ideas, at least.

But okay, I can admit that it’s a lazy answer. We can at least describe some cluster properties, can’t we? I mean, if I pointed at a chair and said “that’s also an RPG,” even if everyone agreed, we would also have to admit that the chair-kind of RPG was different than all the other RPGs in some significant ways.

There are lots of different aspects of RPGs, and none of them are constant or consistent throughout the medium. One of the most common traits, however, the one that seems consistently present in all forms of RPGs, is the simple act intrinsic to the name: roleplay. So perhaps that’s the baseline definition: an RPG is any game where the players pretend to be someone or something they are not.

Brilliant, isn’t it? A Roleplaying Game is a game where you roleplay. This is what a liberal arts degree gets you, kids.

So to improve our definition, we can look at other common patterns throughout the RPG medium: RPGs usually involve groups of players creating a story through shared narration. Each player usually has one character whom they represent — a personal persona of some kind — whose actions they have sole jurisdiction over.

These characters are not exclusively imaginary: they are often codified on paper and given numerical statistics of some kind, like their physical strength or natural charisma. What equipment they have on them, what abilities they have, and what their pronouns are could all be important in the story, and are likewise noted.

Often, one player doesn’t play a single character but instead plays everything else — all the extras, the monsters, the weather…this is the Game Master, or GM. They know the rules, the secrets, the maps, everything that it is the player’s duty to discover.

Inevitably, the players will be challenged in some way, either by monsters, an antagonist, or a simple obstacle like a locked door. The players will decide how their characters try to overcome the obstacle, and then roll dice, draw cards, or use whatever method the system dictates to decide if the action their characters take is successful or not.

Are these traits universal? No, not at all. There are games that subvert, reject, or evolve every one of these concepts, but I think it’s a good enough place to start. Consider, then, that the more a game engages with these traits, the more “RPG-like” it is.

Keep those traits in mind. A group of players, a GM, Dice, Character sheets, playing a role, and all in service of creating a shared story.

So…now what?

There are a hundred different directions we could go in. We could do a deep dive into every game system we can get our hands on, from the mainstays of the 70s and 80s to the newborn indies from the 2020s, dissecting their rules like scientists. We could do market analysis of the most popular games and discover connections between what kinds of games were connected with which societal movements, as one might do with the Punk and Metal genres of music. We could do the reverse and detail the social influences on the medium, including the Satanic Panic and the Mercer-effect. We could do what no one ever seems to do when talking about fan cultures and go to the fan forums and hold interviews with the lay-folk and take their self-reporting at face value to discuss the culture from a journalistic — rather than anthropological or sociological — point of view.

And maybe someone will do all that, someday.

Me, I’d rather just write about some RPGs and the fascinating things that popped into my mind.

First, to get all Hegelian about it: if D&D is, in some shape or form, the Thesis of “what is an RPG,” then what is the antithesis? Is there an anti-D&D?

There is, and I’d like to talk about that next time.