Paradox Perfect, and Timing the Action

Paradox Perfect is, quote: “the improv comedy sci-fi TTRPG of absolute absurdity and chronological chaos! Generate a bizarre Utopian future, roleplay even stranger time-travelers to defend it, and embark on an adventure through history to save the timeline from alteration - before your past, present, and future change along with it!” Paradox Perfect uses the standard die rolling mechanics of a Forged in the Dark game; rolling d6s and calling 1-3 a miss, 4-5 a hit with a complication, and 6 a straight success. In addition, however, this silly game about time travel has an additional mechanic: Resolve.

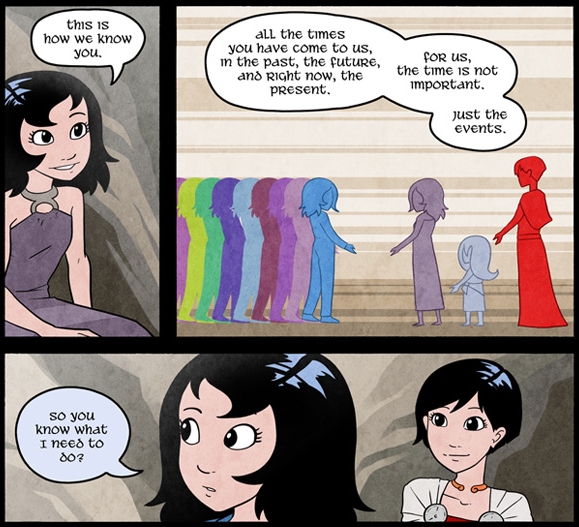

Resolve is a time-travel mechanic which fundamentally does little more than give bonuses, an extra turn or two, or allow for a single retcon. You gain resolve similar to how one might gain inspiration dice in D&D: through good roleplaying and creative problem-solving, or just being really funny. You can’t jump back in time to the beginning of the game using Resolve, for example — that’s the purview of the game-narrative — but time-travel abounds in the world-building; the whole conceit of the game involves paradoxes, time-tricks, and playing around with cause-and-effect.

Speaking of time: when do you roll in an RPG?

Most RPGs recognize that not everyone has played an RPG before, and so have a section in their rulebooks devoted to “how to play an RPG.” Its fun to see how different teams and game-creators explain the experience of rolling dice in RPGs. Most often the intricacies are glossed over and the book merely says “whenever you want to do something that you might not succeed at, you roll to find out if you achieve your goal.”

GM rulebooks, if separate from the non-GM player books, generally go into a bit more detail about when to ask for rolls. Some place the bar at “if there is a chance for failure.” Others raise the bar considerably to “if there is a dramatic branch-point, where both success and failure will advance the narrative.” Some urge fewer rolls with the view that too many will slow down the important part of the game — telling the story. Still others leave it entirely up to the GM, but few actually delve into the idea of why we roll dice.

I touched on that with diceless games already, so I want to re-frame that question: “when do you roll in an RPG?” I don’t mean when in the meta-narrative — when do you stop what you are doing and pick up the dice — I mean when in the game-narrative. I don’t mean when do you roll, I mean if your character is climbing a rope, or swinging a stick, or chatting up a priest, when does the roll take place?

Consider everything that goes into a person swinging a sword. First, they have to think about swinging, gage distance, then they need to wind up, aim for their target, then let their ferrous lever fly. When is the die rolled in that process? Rope-climbing is just as complex: do you roll the die when the character’s hands first grip the rope? Half-way up? When their foot reaches a crumbling foot-hold? Or even before the idea forms in their head?

It may not seem like an important question to answer, but as with all seemingly innocuous questions, the answer has implications.

For example, most games presume all dice are rolled to assess the effectiveness of an attempted action. Your character has an idea: “I want to punch this Nazi in the snoot.” They lift their fist, swing for the schnoz, and then you roll the die. What happens if you fail your roll? Most games just go with “you miss.”

That’s all the meta-narrative requires, but this shortchanges the game-narrative. If you want the game-narrative to model this failure, there are only a few options open to you. Perhaps the Nazi leaps back too quickly. Perhaps you were blinded by rage and misjudged how far away they were. Perhaps the Nazi is far more skilled as a close quarters combatant than you surmised and catches your fist in midair.

Now let’s have some fun: what if the roll happens right after the idea, but before your character takes a swing? In that case, you have more options: perhaps the failure represents the character looking at the Nazi, sizing them up, and thinking one punch isn’t worth the risk of combat. Perhaps they are bamboozled by the Nazi’s smug demeanor, or wary of the brutish thugs glowering behind him. Perhaps the character realizes there is a smarter time and place to punch this particular Nazi, and decides to bide their time. Perhaps the Nazi, in turn, recognizes the look on their face and lords it over them, that they didn’t even dare raise a fist.

See, placing the roll before the actual action increases the narrative flexibility of the action itself. Success and failures can be framed differently; instead of a die roll deciding if a specific punch is successful or not, it could decide if the punching even happens.

How about the roll happens before the idea? Your character may not even consider punching the Nazi, having decided the proper way to deal with Nazis is calm and respectful discussion in the marketplace of ideas, or maybe poison. Your character may still want to see this Nazi on the floor, but rather than needing to consider punching the nazi and backing down, now they can always have had a completely different plan in mind.

Now the die roll isn’t affecting the character directly, but the narrative. It’s not deciding if punching happens, but if “punching” is the way the story progresses.

And these timings aren’t exclusive. If you roll before the idea enters your character’s head, you could still end up swing-and-missing the Nazi snoot if you like. The timings don’t dictate framing, they simply free up framing.

You may recognize this as a more narrowly-focused example of the Intelligence Problem. If the point of a game is to test a player, than the ideas and plans all happen in the player’s head, not the character’s. Saying the character decides not to punch the Nazi after a failure isn’t a result, its a retcon. It’s winding the game back like a tape.

It’s time travel.

Time travel as a concept is rarely done justice in science-fiction. Or rather, it’s rarely explored in the way that we might explore the impact of warp-drive or free-energy. Time travel is such an awkward narrative conceit that there are multiple rules governing its inclusion in any story. Are we playing by 12 Monkeys rules, where the time-line is unchangeable? Are we doing a Sound of Thunder deal where crushing a bug could destroy the world? How about Doctor Who rules, where time and the universe are too big for the idea of “changing things” to really matter? (excepting, of course, for dramatic moments when its suddenly forbidden.)

Video games with time travel are usually experimental, simplified, or use the concept as its core focus. Time travel is either another tool, like jumping or attacking; or its a “do-over” button, designed to keep play fluid.

As for RPGs, time travel has mostly avoided the mechanical side of the game, mostly because so much of RPG mechanics are designed to influence the narrative. We play characters who have a linear view of time, so we follow them as they travel back and forth through different time zones.

Spending “time energy” to allow players to modify when and how a die is rolled is a creative and elegant method of integrating narrative flexibility into the game ludo-narratively, but let’s look at another type of time in RPGs. After all, time impacts games in a lot of different ways: how do we handle time in the meta-narrative?

Next time, I’d like to talk about real-time RPGs.