Mörk Borg and Ending the Game

Mörk Borg is grimdark, apocalyptic, and born from a mix of doom-metal album cover and fever dream. It is rust, rags, and rotten meat. It is rules-light, and tone-rich.

First, let’s talk about violence. Combat in Mörk Borg is simple enough. It borrows heavily from the d20 systems you’re familiar with; roll a d20, add your bonuses, and if you roll over the difficulty rating, you succeed.

The difficulty rating is 12. It’s always 12. Enemies never roll, similar to Knave, and you either roll over 12 to hit, or over 12 to dodge. The difficulty is constant no matter which monsters you’re fighting against.

In combat, a constant difficulty does away with a lot of arguably unnecessary math. Yes, it means that a lumbering zombie is as difficult to hit as a nimble wolf, but what does “difficult” mean in an RPG? Narratively, every combat is difficult in its own way. A wolf might be hard to hit as it jumps from side to side, while a lumbering zombie might be easier to hit, but harder to hit hard enough.

As I said earlier about player-facing rolls, they give the players a strong sense of agency. It is their choices that drive the action, their actions that drive the story.

But.

This player-facing combat rolling contrasts with another mechanic of the game: The Calendar of Nechrubel.

The world of Mörk Borg is not just dark, it is dying. The two-headed basilisk is delighting in their cathedral, watching the land split in a million shards of blood, rot, and dust. The only ones with hope are the foolish necromancers, seeking to animate lifeless bones back into their macabre dance. The world is ending. This is not a post-apocalyptic gameworld, it is the apocalypse.

So, every in-game dawn the GM rolls a die ranging in size from a d100 to a d2, depending on how neigh of an end the players want. If a 1 is rolled, a random Misery — a symbolic omen of cataclysm and the end of days — is inflicted on the world. People turn against each other, the skies rain blood, all the trees die, fathers cry for five days and five nights, swarms of flies, rivers turn to tar…it is the end of the world.

The seventh Misery is always the same; the seventh seal breaks for the seventh and final time. Darkness swallows the darkness. The game ends. The last sentence of this section: “Burn this book.”

When does an RPG end?

Well, when you win, right? Seems obvious.

But as I said before, “winning” in RPGs, as in life, is a nebulous concept. Most games and sports have defined endings: reach the end of the path with the most victory points, have the highest score after an hour of play, or kill the dragon without dying. The Foozle is killed, the McGuffin is found, the heroes wander off into the sunset, curtain, lights.

Stories are different things, but they too have endings. To “win” is a bit of an awkward way of putting it, but you could still say reaching the end is a “goal.” After the climax and a bit of falling action, the end of the story is the end of the RPG.

You can mash these two concepts of winning together pretty easily. The story of our party killing the dragon ends when we kill the dragon, and that’s when we win. Simple, easy, and elegant.

But you can quit, right? You can get bored, or irritated, or a sudden life-crisis might prevent you from continuing the game. I’ve had games end before they’re finished, as have you, I’m certain.

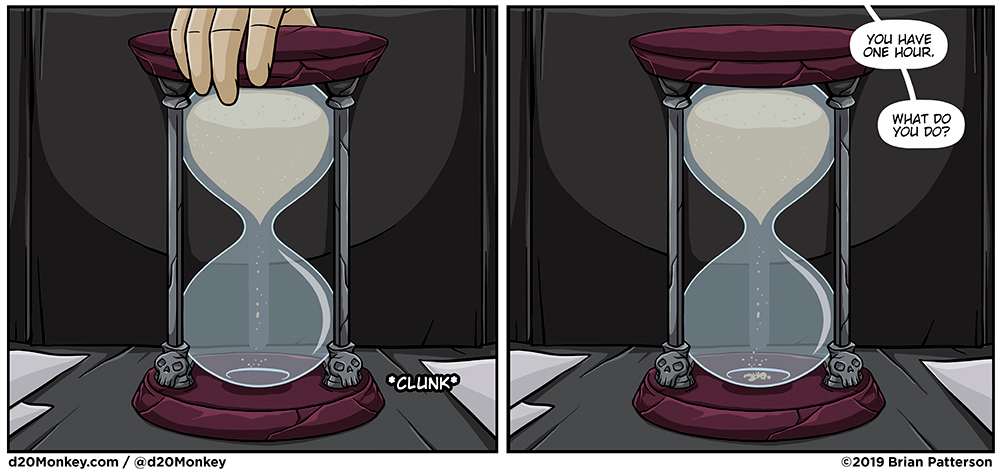

Mörk Borg says that endings don’t have to be the purview of the story, the game, the GM, or the players. Mörk Borg says the ending is the responsibility of time.

What do RPGs look like when they’re timed? Hackmaster is a game that prides itself on its speed, urging the GM to have players lose their turns if they think too long about what to do next. Minigames can use timers to help urge the players into a state of near panic as they think as quickly as they can, working on instinct rather than mathematical analysis.

Longer-term clocks can keep players focused: a deadline of seven days before reaching the planet gives players incentive to hunt for a vaccine before they risk a global pandemic. Three days before the next full moon gives the players a clear idea of how much time they have to prepare before the werewolf strikes again. High-tide will come tomorrow morning, and then the murderer can escape, never to be seen again.

But these timers all center on the subject of the story: the disease, the werewolf, the murderer. In Mörk Borg, the timer is for the game itself, and it could hit at any time. How many dawns pass as your characters wander from desiccated ruin to desolate city? Two weeks is fourteen rolls. How many 1s could be rolled in a month?

And when the final roll is made, where will you be? What will you be doing? Will the earth fall to dust as you finally plunge your sword through the fell-serpent’s throat? Will you be heading home after slaying the evil Skull-King? Or will you still be climbing the cliff to reach the Skull-King’s castle? Will you be in a tavern, asking for rumors on where to find the last Jade Star Jewel? Will you be halfway through a sidequest? Preparing to set out on a new adventure? Will the world end too soon?

But only players roll dice in combat. They roll to hit, they roll to dodge.

It is a fascinating experiment in player agency. The ludo-narrative plays both sides of the spectrum, offering players the right to exclusive control of their characters, while taking away the simplest control of all; when the story ends. It might be fitting, it might be upsetting, it might be wholly unfulfilling.

You need to be in the right mood to play Mörk Borg like this. It’s not a game about empowerment, but rather embracing the Camus-esque absurdity of the Conqueror. Players must accept the fact that the world is ending, they cannot stop it, and yet choose to play the game anyway.

What might that do to you, as a player? What kind of character would you make?

We are all transient. So too are our legacies, whatever kind they may be. The stars will not burn forever, and someday everything shall return to darkness.

What would you do, if you knew for a fact that nothing you did would ultimately matter, and more importantly, matter in the near term? Would you be less likely to risk your life to save another, knowing that you might only be gifting them with two more months of life? Our would you be more likely, since you might only be risking a few weeks yourself? Would you study forbidden dark magics, embracing the side of yourself you always suppressed? Would you become a pacifist? More loving? More spiteful?

Does the inevitable futility of your efforts make your actions all the more pointless?

Or not?

As I have said before, RPGs are excellent ways to experiment and practice situations before we are confronted with them. Obviously, our entire world literally exploding is not something we need to prepare ourselves for, but climate catastrophe is coming for all of us, and we won’t always know when.

And even if it wasn’t, this is not a game about dealing with the end of the world. The Calendar of Nechrubel is not tied into the game in any other way. It’s a minigame. It’s tone and flavor. It’s ludo-narrative structure. This is a game about asking yourself one simple question: Why are you doing this? What’s the point?

A difficult question to answer at the best of times, when treated with the respect it deserves. We will all die someday. It can be hard to accept this about ourselves, harder to accept about our parents, and harder still to accept about our children, their children, and their children’s children.

But we adventure on. We keep rolling the dice, turning the page, asking the question “what happens next?”