.Dungeon, and Augmented Reality

.dungeon is a pretty simplistic RPG in a lot of ways. With a MMORPG dungeon-crawling aesthetic, the game taps into virtual RPG simplicity. You assign dice to your stats and roll the dice any time you want to do something. Roll high enough, and you do. Roll lower, and you don’t. Pretty simple rules-light stuff.

But there is one specific difference: .dungeon’s ludo-narrative taps into the meta-narrative of the game. Put simply, the real world affects the game-world.

Well, all RPGs are affected by the real world, right? You roll a die, and the results of the die change the game-world. So what does .dungeon actually do differently? It expands this mechanic to more than just dice, but to a multitude of ludo-narratively symbolic items. Put more simply; if you decide to play as a mage, for example, you need to pick a book and circle words and phrases to memorize your spells. Not an in-game book, mind you, but a real book. A physical book of your very own shelf. Mark it up with a pen, and cross out the phrases when you’ve cast them.

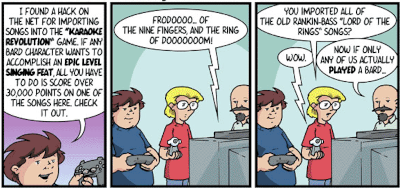

It’s not just mages; if you’re a bard, you need to make a music playlist you can play for everyone at the table. If you’re a knight, you can take vows for a bonus, like the vow of silence which means you — not the character, you — can’t talk. If you’re “the beast,” then you can transform into one of your real-life pets. The Hacker has the ability to just straight up cheat.

When we play RPGs, our hope is that our concerns, our pains, our problems in the real world will be set aside for the moment. That Thug the Barbarian doesn’t have a term paper due in a week. That Wizar the Wizard doesn’t have a Employee Assessment meeting tomorrow. That our stresses can be escaped for just a brief period of time.

Its rare that games outright reject this fourth wall. Mythic Mortals certainly does its best, but comes at it from the opposite direction. In Mythic Mortals, you play a super-powered character who is you. You don’t have these mythic powers, “you” do.

.dungeon pulls the ludo-narrative in the other direction, saying you do have power. Not by virtue of holding dice in your hand, but through your promise to keep silent, your favorite music, and your shelf full of books. The real world has just as much power over this fantasy world as the dice do.

I’ve heard these kind of games called Augmented Reality Roleplaying Games, or ARRPGs. These games split the difference between LARPing and tabletop play, bringing real-world actions and objects into the play-space, breaking down the wall between world and imagination. In practice, dice are oftentimes our only practical connection between the real and the imagined worlds: the act of rolling the die is the concrete and external means by which we make things happen in the fiction. ARRPGs utilize player-behaviors as an alternate method of doing the same.

As players, we are sometimes asked to give of ourselves to the game. Either we are asked to become vulnerable in ways both big and small, from allowing our power-fantasy to be marred with disempowerment to simply accepting that our earnest attempts can fail; or we are asked to give of our absence, to keep our insecurities and our traumas from interfering with what the character would “actually do.”

This is how we interact with a fake world. Dice are our limbs, and character sheets our bibles. We keep the real and the fantasy at arms length from each other to keep the illusion going. The point of roleplay is to be someone or something that we aren’t.

.dungeon isn’t the only game to question this: Rogue 2E, for example, gives character’s Aces — special abilities that refresh after 15 minutes of real-time — while Inspirisles uses sign-language to work the magic system. Starting a session with a prayer in Heroes of Adventure can give religious characters favor points that can be used for in-game miracles.

And then there’s LARPing. LARPs do their best to do away with the distinction all together, asking you to move and speak and fake-fight in meatspace rather than the theatre of the mind.

LARPing has always been looked askance at by outsiders. If RPGs in general were seen as nerdy or weird, LARPs were viewed as outright bizarre at best, dangerous at worst. The act of traipsing about in the woods wearing costumes is just a hint too close to the absurd fears of a Witch’s Sabbath to be warmly embraced by some of even the most openminded of outsiders.

But LARPing isn’t just shouting “fireball” at an armored data-analyst from Indiana. There are LARPs that do more than just get you out in the fresh air. If I wanted to give this post an R rating, I could try and fail to find any significant differences between LARPs and roleplaying in the bedroom. (Yes, there is one quite significant difference, but as I am pure as the driven snow, I don’t know what that difference is.)

When the fourth wall is broken, bent, or even simply addressed, we are forced to confront how the imaginary tools that roleplaying uses are not solely the purview of the fantastical. Devotion, generosity, compassion, courage — these are not the purview of our personas alone.

It is my playlist that boosts my fellows. It is my book that slew the dragon. It is my silence that gave me a boost to my rolls, much the same as it was our compassion that made us accept the quest to slay the evil tyrant, or our courage that kept us from turning back. It is our choices that influence the world around us. It is our hands that build tomorrow anew every morning.

We adventure together. We thrive and strive by working together. It is not our personas alone who can be heroes.