Noblesse Goblige, and Minigames

Noblesse Goblige is a competitive GMless RPG based in Verdibog, a cosmopolitan goblin city in a swamp. In it, you play as a scion of one of five major goblin clans, each of which has a claim to the title of Gob-Boss after the current Gob-Boss, Lady Stinkworth, died without naming a successor.

Each player plays a character from a different clan, each with the goal of manipulating their way to the top of the successor list, bringing power, prestige, and lots and lots of money to their clan. Only one can be crowned, so political backstabbing, frontstabbing, and actualstabbing is in everyone’s near future.

Being a competitive RPG, a lot of the mileage you will get from the game will depend a lot on who you play with. As I mentioned in my post on Mission Accomplished, “competitive” can mean different things and play very differently, depending on how you want to view “winning” in the game. Make sure you know who you’re playing with, and ensure everyone knows their responsibilities.

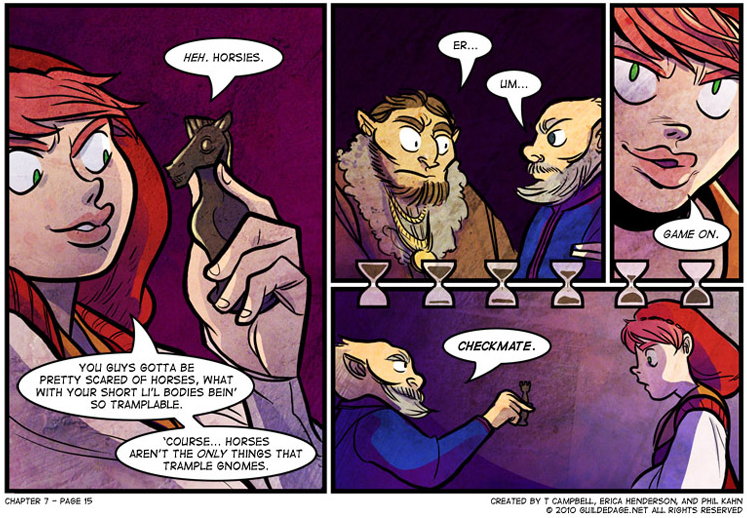

But competitive or not, Noblesse Goblige is a great game to introduce another aspect of RPGs: the minigame.

Noblesse Goblige begins with building the setting, describing your unique Verdibog, creating your characters and their personal relationships, establishing rumors, draw a hand of cards, and finally commencing the “Remembrance of our dear Gobmother” scene. This is Lady Stinkworth’s wake, where the characters all meet up, mingle, and eventually leave again.

This scene is the first minigame of many.

A turn in Noblesse Goblige works like this: First, the player may chose to do one of six “quick actions,” such as making another player reveal their hand, discarding cards to perform a ritual, spread rumors, or reshuffle the discard back into the draw pile. After that, the player chooses a minigame to play. These minigames range from sowing chaos in the other clans to stealing time away for a secret tryst. Each minigame is likely to result in spent cards, a shift in notoriety tokens, and an acted out scene of upper-class goblinism.

The term “minigame” was invented (as far as I can tell) for video games, to describe the small self-contained games that were a subset of the larger game as a whole. In RPGs, minigames are a slightly more nebulous term. In some cases, minigames are similar to their video-game counterparts; a subset of rules largely distinct from the greater whole. Inventory management could be a minigame, as encumbrance rules are rarely significant beyond your backpack. Long-travel could also be a minigame, with prices for different kinds of transport alongside risk percentages and supply costs. Fortifying a town or developing a settlement could also be a minigame, depending on how it’s handled.

But if that’s our only metric — rules that apply for only a given situation — then almost anything is a minigame in RPGs. Attack rolls never matter outside combat, and you’re not going to use your Social Etiquette skills when you’re sliding down a mountain. If you wanted to, you could make any action that comprises an extended period of time use an entirely unique set of mechanics. (Much like adventure games use distinct puzzles for unique circumstances as opposed to the action-game ethos of a small number of easily repeatable behaviors see more in Ian Danskin’s Who Shot Guybrush Threepwood okay I promise I’m done talking about it.)

This is the ethos used by games like Dueling Fops of Vindamere, Ocean Tides, For The Honor, and, of course, Noblesse Goblige. In Noblesse Goblige, these scene-length minigames make up the entire RPG until the Willowing Moon rises and one of the goblins is chosen as the inheritor of the title of Gob-Boss.

This implies that what makes a minigame a minigame is not the particulars of its ruleset, but its demarcation from the rest of the game. If everything else “pauses” while we deal with this situation, you could call it a minigame. Even if it’s not a full pause, as long as the situation isn’t directly tightly connected to the overarching gameloop or narrative arc, it’s a minigame.

Some might could argue that these are not so much “minigames” as they are “scenes.” Most RPGs use “scenes” as a method for delineating time passing. Much how we don’t bother roleplaying the walk from one shop to the next, we can just fade to black on one room, lights up on another. Each scene isn’t its own separate “game,” is it?

Well, what if it was? “Fighting the Orc Scouts” could be a minigame, as could “Persuading the Bouncer,” “Gathering Information about the Parade,” or “Purchasing Supplies for the Trek.” Most of these scenes don’t influence any others, apart from the results. Does the King need to know anything about your fight with the goblins other than if you won or not? Once you have your information about the Parade, does it matter if you bought it, overheard it, or charmed it out of the town drunk?

In fact, a lot of GM tools could be used to manufacture minigames. Clocks and progress tracks could be raised or lowered based on players actions, representing the prosperity of the region. Donations to different organizations could result in improved equipment or better services for the player’s efforts. It’s a cheap trick, but giving things numbers is always a good way to elevate a narrative conceit to a game mechanic; saying a region is starting to prosper is all well and good, but for some players it will mean more if they can see a “Prosperity: +1” over the townhall on the map.

But if we buy into the framework that rules and game-narrative are in opposition, does this mean that minigames cannot be used in a fiction-first style of play?

One of the interesting aspects of Noblesse Goblige is how tied to the narrative its minigames are. Most of the minigames involve drawing, playing, comparing, or discarding cards; and getting or losing notoriety tokens. There is, in fact, little mechanical difference between the minigames.

What’s different is the narrative. In each minigame, the players answer questions about what their scion or clan is doing or feeling in regards to the situation. The clash between clan Fanglington and clan McGobb means something different, depending on if clan McGobb is furious at Fanglington for stealing away the heart of lovely lady Snagg McGobb, or if Fanglington started the fight to prove their strength to the stuffy old Slalizzar clan.

This fiction is what drives your characters. You may not know which minigame is strategically “better” than another, but if your scion is set on proving their financial acumen to their clan, then they’ll certainly want to organize an auction. If the last minigame resulted in your scion being insulted as low-class, then they may want to organize a Verdibog Cultural Faire to show off. The marriage minigame probably won’t happen unless some wooing has been going on. It’s all as much narrative as mechanics.

And not to leave it unsaid, you obviously don’t have to make a game out of minigames. If the point of minigames is their demarcation from the rest of the game, then they are — by definition — modular. There’s plenty of them; they gamify everything from cooking to farming, dream sequences, playing games (how meta!), and more. You can use them or not as you see fit. You want to try it, try it! You want to make your own? Slot it in! Feel like this one is an unnecessary complication? Tear it out!

Now, there is one other kind of minigame that I find fascinating, and that is when minigames spread out into the real-world. TTRPGKids, for example, has minigames for kids that involve gathering colors for potions, or dressing up for dragons.

Masterfully executed segue? You tell me! Next time, I’d like to talk about Augmented Reality RPGs.