Mission Accomplished, and Competition

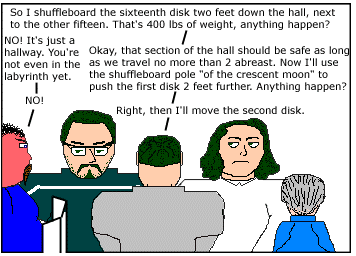

Mission Accomplished is an RPG inspired by shows like Archer, The Venture Brothers, and Better Off Ted. It’s a game about being a team of super-spies who save the world on a weekly basis, usually in 30-45 minute increments. You drop into dangerous situations, mix things up, and then get out of there and back to HQ, a job-well-done.

But that’s only half of the game. The second half is the HR meeting, where the complaining, bickering, and blaming happens. The cooperative game of saving the world suddenly becomes the competitive game of credit-stealing and finger-pointing.

It’s an axiom of RPGs that they are cooperative games. You are supposed to assemble a party of adventurers who will watch each other’s backs, working together to overcome a shared challenge; not stab each other in the back for an extra share of the loot. (at least, until someone roleplays their thief character to the hilt — see my post on King is Dead for more on that thorny problem…)

Mission Accomplished, on the other hand, has a whole half of its game devoted to thwarting your fellow players. What’s that about?

There’s two sides to competition in RPGs, and I’d like to address the non-GM side first: what is Mission Accomplished trying to do? Cooperative play is foundational to the medium. The idea that one player might win while another loses feels more like a board game than an RPG, doesn’t it?

Well, kind of. “Winning” in Mission Accomplished gets your character sent to a black-site where they are torn apart and built up again as a souless wet-work machine. Being the worst spy gets your character “disappeared,” and between those two extremes is a bunch of worthless promotions to desk-duty, being suspended with pay, and “just get the fuck out of my office.”

It strikes me as similar to Fiasco, where there is technically a competition at the end to see “who comes off best,” but the results ultimately don’t matter. Sure, someone “wins” and someone “loses,” but you’re not supposed to be invested.

Direct competition is a terrible thing to add to an RPG: If a game has both cooperative and competitive elements, eventually a player will find a situation where they have to ask themselves “do I help the team at the cost of myself, or do I help myself at the cost of the team?” Playing the game then involves trying to be more selfish than everyone else, but not so selfish that the whole team loses, while hiding said selfishness from the team so they don’t thwart your selfishness in service of their own.

Let’s take a quick look at Kitchen Contest, a competitive cooking RPG. The players play both a Chef and a Judge, and the language in the rulebook encourage a separation between player and character. Players have to “describe your Chef cooking and competing by selecting a fictional action and its outcome.” Then comes the judging phase when “you describe your Judge reacting to the dishes offered.” The players aren’t supposed to put themselves into the fiction, but describe it like observers.

Then again, Duel RPGs like Last Shooting or CROSSED/FATES are based around competitive situations. Someone has to “win” in those games, don’t they? Troupe games like After the War or Girl Underground can rotate “villains” among the group, setting up periodic competition among the players. And let’s not forget games like Monsterhearts or Visigoths vs Mall Goths, both of which actively encourage players to pit their characters against each other for dramatic purposes.

So what is the difference between RPG competition and board game competition? Is there a difference? Or have RPGs just settled more regularly on the cooperative side of things?

I’d say that if there is a difference, it’s that RPGs break the illusion around winning.

You see, we’ve all heard “it’s just a game” before. Ultimately, who wins a game of Monopoly doesn’t actually matter. It’s supposed to be fun regardless who wins or loses. It’s not always, of course, but that’s the intent. Nevertheless, games and sports only “work” when the people involved — on some level — care about winning. They have to try.

RPGs actually embody the “it’s supposed to be fun” side of that argument, and sacrifice the idea of “winning and losing” on that altar. Sure, characters might be able to win or lose a certain engagement, but the players win or lose as a whole. This is why the idea of “winning an RPG” is a bit of a joke. You can’t “win” anymore than you can win gardening.

If an RPG does allow players to “win” or “lose” individually, then the winning or losing won’t make a difference. Either the rewards are superfluous or Pyrrhic in nature, or the idea of winning is more a narrative conceit then a mechanical game-state. Cooperative gameplay is a lynchpin of RPGs; you can skirt it, avoid it, or manipulate it, but RPGs certainly care more about everyone having a good time than being a “game.”

Except…what about the GM?

I skimmed over it before, but when discussing GM-less games I said: “In chess it’s white vs black. In monopoly, it’s shoe vs top hat. In RPGs, its GM vs players.” At the time I said it was reductive, but I never disabused the notion.

This is the second side of competition in RPGs. Is the GM your friend?

Martin TT wrote a great post detailing the description of the GM role from multiple rulebooks from various publishers and eras. Looking through the list, we can see some continuing themes about the GM’s role, but few are as vital as whether or not your GM is operating in a supportive or combative relationship with the other players. Is your GM here to be your cheerleader, or the opposing team?

As with all things, it depends. Endless Lands, as I said before, has different variants depending on whether you want a GM who is primarily an adversary to the players, or a cooperative one who is little more than another player with slightly different responsibilities.

What does competitive GMing look like? Combative RPGs are the games that have most in common with their wargaming roots. In any battle there are two sides — Whether Chess, Battleship, Stratego, or D&D — and each side their own victory over the other. The GM has to try and “win,” working towards the other players’ failure through every rule at their fingertips. The GM’s duty is to make the other players sweat, because the game is only fun if it’s hard.

Supportive games, on the other hand, don’t see this dynamic as particularly useful. After all, a GM doesn’t just play monsters, but also plays allies, mentors, patrons, and neutral NPCs. These games work through collaboration with the GM and the players; challenge may not even be a factor as far as the players are concerned. Supportive games care about good stories, engaging roleplay, and ensuring that players remain the main characters — the heroes of the adventure.

But all RPGs can have allies and good stories, so perhaps combative is the wrong word for it. Neutral, perhaps? Neutral GMs create challenges for the other players and then plays the dice as they roll. They’re not there to offer suggestions, help the players along, or do anything other than tell the players what the consequences of their actions are. It’s less combative and more “oppositional,” the state of the world vs. the other players’ will.

Naturally, Supportive GMs can be challenging and Neutral GMs can encourage great roleplaying; it’s always a spectrum between two extremes. On the one side is a GM who is the builder of the Adventure Game, the maker of the crossword puzzle, the challenge to overcome. On the other side a GM who is a fellow player, working with their friends to craft an adventure worthy of the word.

And let’s not get into the rabbit-hole of Tournament play: As far back as its inception, D&D had tournaments, with modules like The Hidden Shrine of Tamoachan and The Bane of Llywelyn designed to test and rank different players with scoring systems and pre-rolled characters. This created competition between the GM and players, but also other teams.

At the risk of sounding repetitive, neither option is better or worse. As long as everyone agrees on the GM’s role, there’s nothing wrong with either working together, or a little friendly competition.

Just make sure everyone is aware of their responsibilities to the game and each other, and everyone can win, whether they win or lose.

Okay, that’s about as saccharine as I can stand. Let’s move on to Minigames, shall we?