Liminal Horror, and Forcing Emotions

Liminal Horror is a rules-light system for modern horror stories, taking inspiration from places like Silent Hill, Junji Ito, and Silent Legions.

Horror, like any narrative genre, can be applied in different ways. GURPS and FATE can both handle horror adventures, as can D&D with its Ravenloft series, or Blades in the Dark with its ghosts and demons. Any system can tell a horror story, because any game can have horrific things happen in it.

The Horror genre also exists ludo-narratively. Horror RPGs have their own tricks and tropes, just like Horror stories. They usually have some kind of “fright” meter, whether measuring sanity, willpower, or bravery. When something scary happens to a character, their meter drains (or fills) until the character is forced to panic, flee, or be driven mad. Universal systems like GURPS usually have optional “fright checks” or similar mechanics to model a character’s fear.

Liminal Horror does something amazing. Something I love, and want to see more of in horror RPGs going forward. Liminal Horror doesn’t Play Your Character.

What do I mean by that? What I mean is that there is a thorny problem that most non-horror RPGs don’t pay much attention to: what happens when your character feels something that you, the player, don’t? Most games have some method of codifying a character’s behavior; whether Humanity in Vampire, Limit in Exalted, Pendragon’s Virtues and Vices, or even D&D’s famed alignment system, these are all methods focused on measuring how a character thinks and behaves.

The obvious thorn is the player/character synchronization issue we discussed earlier: what if your character is listed as “good,” and you tell the GM that they do something “evil?” The GM can penalize “bad roleplaying,” but it’s rare that a player will do something so blatant. More often than not, such conflicts devolve into the player and GM arguing about what “good” actually means.

But that’s only the first thorn. The more subtle pierce comes from the fact that your character is your character. No one else can play them; not other players, not the GM, not the system itself. You have complete control.

So what happens if your character’s emotions take that control away?

The GM leans back in their chair: “You stare into the beast’s eyes at its roars split the air. Deep in its gullet you see swirling hellfire as its claws tear blood-soaked furrows into the earth, and ichor drips from its horns.”

Are you frightened? Why are you?

I mean, that’s a terrifying description of a monster, isn’t it? If I was level 1, or hadn’t found the demon-slayer blade yet, I’d probably want to run. But that’s a strategic reaction from the player, not an emotional response from my character. Besides, my character is the overconfident protagonist, so I’ll probably just have them draw their gun and say “You’re in trouble now; let me demon-strate.”

Not quite tone-appropriate in a horror game, is it?

On some level, this is a “good roleplay” problem. If something is scary, you should have your character behave like they’re scared, but that can be a hard ask when you’re supposed to be a heroic adventurer staring down death and thwarting the evil villain.

So most games “gamify” character emotions as obstacles. Some games rely on conditions: the Demon Roar ability may cause the “frightened” effect on everyone within seven squares, and anyone who is “frightened” has to run as far as they can on their turn. The rules clearly say so. Or maybe being “terrified” means you receive a penalty if you try to affect what frightened you. We can’t have you behave incorrectly; if something is frightening, you have to act frightened.

And then there’s Cosmic Horror and “sanity.” Call of Cthulhu is the most famous example, and it’s…really insensitive.

I mean, the world has changed a lot since the early 80s, much less the 20s when Lovecraft was doing his reactionary thing. “Sanity” is as much an outdated concept as the four humors; but this is a game and that means we have to have a mechanical measure of “horror.” Eventually, the character loses all their sanity hit points, and the character now has to act “crazy.” In narrative, in roleplaying, in improv, this is called Playing Someone Else’s Character. You don’t do it. It’s taking control away from the one thing that you are usually supposed to control in an RPG.

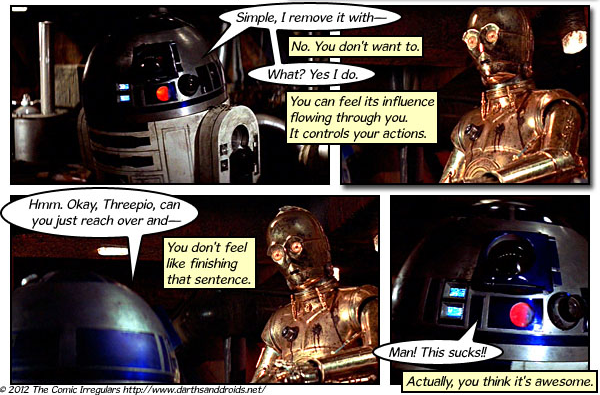

And that’s before we even get to the more exotic examples of being charmed, enthralled, romanced, enraged, or any other number of emotional conditions that might be forced on your character. Whether magically or mundanely caused, the Rules are controlling your actions by telling you how you have to feel.

While the ideal solution to this is to have situations that charm, enrage, or frighten the player, and therefore encourage them to play their character accordingly, there is no reliable way to manage this. Descriptions that fall flat can come off as campy and silly instead of horrifying. Characters might be scared of something that the player isn’t scared of, or visa versa. And when push comes to shove, the characters are the ones in actual danger; we’re safe and warm at the dinner table with the lights on.

In Liminal Horror, on the other hand, your character’s “Fallout” results in possibly shifting their stats or being given a narrative hook to play off of. As the horrors of the story continue to swarm and coalesce around the protagonists, unnatural things begin to manifest. Perhaps your character feels hunger for something inappropriate, or starts getting followed by an unopenable door. The world starts to “go mad,” rather than your persona.

This is a brilliant solution because it keeps character control squarely where it should lie: in the player’s hands.

Of course, that might be a bit too far for some GMs. They may want things to terrify characters, whether their players want it to happen or not. Sure, it’s not like inflicting emotions on our characters is impossible to do sensitively. As always, consent is key; especially if your players are here to fulfill their power-fantasies, having that single most important power — self-determination — stripped away from them without their consent can be frustrating.

Or triggering: being told how you feel is a common method of emotional abuse.

You could simply do away with mental-control effects altogether; no charms, no seductions, no infectious madness. Leave the character’s behavior up to the players. The GM has to come up with clear descriptions and evocative language to allow the players to roleplay fear or romance if they wish.

After all, what effect does a charmed player give a game that can’t be tossed out? Can you think of a story where mind-controlling the hero was a useful or interesting plot point?

You can? The climax of The Lord of the Rings? Huh…

Okay, well, if you’re set on including such magics, then let’s consider another alternative. Instead of dictating tactics or goals to a mind-controlled player, why not just take control completely? If a player gets seduced by the One Ring, don’t be an auteur director, asking your actor to “give me a take where you love the ring.” Instead, tell the player to relax for a bit, maybe take charge of the hireling, and turn their primary character into an NPC. This is ludo-narratively consistent if the character is suddenly “not in control of themselves.”

Or, you could consider letting the players roleplay it how they want. We can’t chose our emotions, but we can sometimes chose how we handle them. Perhaps the brooding loaner is enthralled by the succubus, but pines away in the shadows instead of doing what they are commanded. Maybe the battle-scarred veteran is so cynical when it comes to love that she tamps down her feelings until they become just one more emotional scab.

Perhaps the best example of this is the spell Presence from Troika! The spell’s effect, in total, “makes the recipient feel watched by a paternalistic gaze.” What on earth does that mean? How would that effect a player if it hit them? What situations would that even be useful in?

Well, the answers are all right there in the description; it affects a character or NPC however it would affect them. Maybe my character is a devout follower of the Divine Family, and feels emboldened knowing that their Holy Father is watching. Perhaps they feel anxious, the pressure to make-proud overcoming their confidence. Maybe they burst out sobbing. Maybe they roll their eyes and carry on. The point is, it is up to the individual how this mental-control effect manifests.

This is primarily a tool for narrative games and will require some strong flexibility on the GM’s part. If this feels too loose, like the GM is sacrificing control over the game, well…yes! That’s the point! As a GM, you’re going to have to admit to yourself that sometimes, your fellow players just aren’t going to feel what you want them to feel.

But gamifying emotions is only half of the story; Characters have emotions, yes, and how those emotions impact the game can be an intriguing question to explore, but players have emotions too. The whole point of creating art is to communicate thoughts and feelings, with the hopeful intent of eliciting thoughts and emotions in the audience.

Next time I’d like to talk about what happens when this goes wrong.