Ironsworn, and Clocks

Ironsworn, set in an iron-age dark fantasy world, is a game about survival. To quote the game itself: “You will explore untracked wilds, fight desperate battles, forge bonds with isolated communities, and reveal the secrets of this harsh land. Most importantly, you will swear iron vows and see them fulfilled — no matter the cost.”

The mechanics of this game are quite interesting to me, but I want to focus on one specific design choice; everything — from a single combat to the campaign as a whole — is represented by progress tracks.

What are progress tracks? They are, for all intents and purposes, Clocks.

Clocks are a useful tool in RPGs, especially capable for tracking goals that take time, rather than a single result roll. For instance; a single roll might be fine for deciding whether you pick a lock or whether your bullet finds its mark, but is it really enough for cooking a meal, driving a car in a chase, or hacking a complex computer system?

It could be, if you want to get to the important part of the scene — the tense dinner conversation, the shootout at the bank, or what’s in the hidden files — but surely the act of cooking, driving, and hacking can be as dramatic as what comes after? Cooking is a long process and meals can have more than one course. Bumps on the road might make someone drop a gun or hit their head. Hacking can be complicated by guards marching ever closer on their rounds.

Enter the Clock; a means of measuring the distance a character is from a specific event over a period of time. If you play D&D, you’re familiar with “death saves;” it’s the same idea. Mechanically, a clock is a certain number of boxes that must be checked before a result is reached or a situation is over, whether in success or failure. For example: if you’re chasing someone through a crowded marketplace, the GM might ask for series of skill-checks to detail a scene of jumping over carts (acrobatics), shoving through crowds (strength), darting through back alleys (notice), and so on, until a certain number of successes are reached, or the target escapes.

Clocks are also a method of smoothing out long-term contests. If the whole session is based on sneaking through a mansion, there are multiple times when a player might fail at being stealthy: Linoleum floors, security cameras, the laser grid, guard-routes and locked doors, all of which could reasonably require different rolls to see how the persona manages.

But even with just those examples, that’s five possible rolls. Does one failure mean the dogs are at your heels as you run for the exit? That means you need to succeed five times in a row to “win” the stealth minigame. Statistically, that’s a lot harder. This is usually mitigated by having a “failure” clock as well, requiring you to fail two or three times before the alarm sounds and your cover is blown for good. Practically, this method mitigates unlucky rolls, reducing the effect bad luck has on a player’s efforts.

Ordinarily Clocks are great for this kind of obstacle, but Ironsworn takes it one step further. After all, isn’t combat a race to do more damage? Isn’t a chase a combat of running instead of blades?

Combat in Ironsworn is not a series of attacks and parries, but a series of successes and failures that move each side closer to their ultimate victory over their opposition. That victory could look like a pile of dismembered corpses, or a single sword-stroke through the heart. A hundred axe-blows that tear apart a foe’s armor, or a series of sword-clashes without a single strike hitting flesh. No more parry-thrust attack-dodge mechanics, combat is a story, as significant and complex as any other obstacle your heroes encounter.

Consider the sword fight in The Princess Bride. I’m not going to say which one, because you already know which one. How many dice-rolls were rolled in that fight? There are three possible answers to this question:

Answer 1: Too many to count.

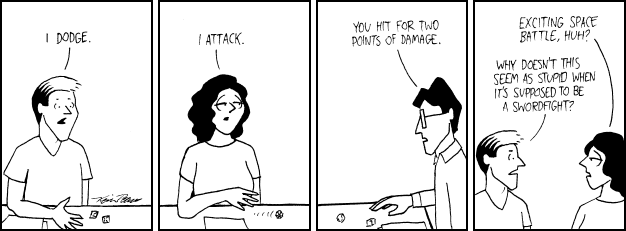

This is the traditional parry-thrust action roll of most combat-focused RPGs. An “attack” is more or less a single sword-swing. Maybe two or three if the narrative is given some leeway, but functionally, this is the system-first style of combat. A single attack, whatever its narrative excuse, is counted a success or failure by a single die roll. You swing the sword, does it connect? You cast a spell, does it work? You dodge an arrow, are you fast enough? Action rolling makes for a tense experience but also allows for player flexibility. If one attempt fails, they can adjust mid-stream to a new tactic, change targets, or flee.

Answer 2: One and only one.

This is the result roll option. A single roll is made at the beginning of a long-form action, and is used to dictate the outcome. Details are then provided as desired by the involved parties. In this case, after both swords were drawn, Westley and Inigo rolled their combat dice. Westley won the roll, so both players knew who was going to win; the only question was “how?” Perhaps they talked it out, perhaps the GM dictated.

Answer 3: Six.

That’s…oddly specific. Let’s look at the action beats of the fight-scene. What actually happened?

1: Inigo pushes Westley back with his swordplay, up the rise and forcing him to jump down before flipping down after him. 2: Now, Westley pushes Inigo back towards the edge of the cliff, until Inigo switches his sword-hand from left to right. 3: Now it is Inigo’s turn to push Westley up the stairs, pinning him to the wall before Westley pulls the same trick and switches his own hands. 4: Westley disarms Inigo, forcing him to swing on the bar to go after it. Westley follows with consummate flair. 5: Westley now pushes Inigo up onto the ruins, before disarming him again, sending his sword into the air. 6: After Inigo catches the sword, Westley pushes Inigo back some more before disarming him a third and final time.

You might divide the fight differently, but regardless; each beat could easily be a single die-roll that advances a combat clock. This is the kind of combat that Ironsworn encourages; a single roll doesn’t describe a specific action per se, but rather a sense of momentum. Inigo succeeds on their roll, taking control of the fight. Then Westley succeeds on their roll, forcing Inigo on the back foot. Then Inigo succeeds, switching hands to explain their sudden burst of effectiveness. Westley succeeds and pulls the same trick, a suitable excuse in a comedic game. The gymnastic-bar bit could easily be a tie. Another victory for Westley results in a flared disarm, and a fourth and final success results in Westley’s victory, 4-2.

While Ironsworn’s combat will certainly be different tonally, with its harsh and gritty world, the framework is the same. The point of each roll is to shape the action, not dictate nor side-step it.

I haven’t harped on this fact, but it’s important to note that Ironsworn doesn’t just handle combat with progress tracks, but everything. From individual quests to the game’s campaign as a whole. This ubiquity of the mechanic is integral, I believe, to what makes Ironsworn fascinating. Similar to FATE’s bronze rule — everything is a character — in Ironsworn, everything is a progress track.

So…of the three types of die-rolls, which is best?

That’s a pretty subjective question for an objective system to answer. Whichever is more fun for you, obviously. After all, in previous posts we looked at how action rolls and result rolls both affect a game, and I asked if there was a compromise between the two.

I think that clocks are a lovely middle ground. They allow for creativity and flexibility in results, while not eating up time with extensive strategizing and die rolling. They allow for depth in situations without being too fiercely bound to the luck of the die. They can be applied to almost any situation, giving each situation a level of complexity and surprise while keeping narrative at the forefront. I think they’re worth exploring.

But all of this is based on one basic assumption; that dice are the best way of deciding what happens next. Next time, I’d like to start questioning that idea.