Badger + Coyote, and Tactical Conversation

Badger + Coyote is a GM-less dual RPG. One player plays Badger, the other Coyote. Asymmetrical in design, Badger has skills that allow them to do things in the game, such as digging, trapping, and sniffing. Coyote, on the other hand, can only spot, pounce, or make a roll to “speak” a sentence to badger, who can then respond. This is the only way that the two characters can communicate to each other.

Its a fascinating design, using the standard skill-separation in most class-based RPGs (soldiers shoot guns, mages use magic, thieves open locks, etc.) and pushing them to their extremes. Badger “does,” while Coyote “talks.”

What it also manages to do is make conversation a fundamental tool of play.

It’s not like most games don’t. Longer conversations are integral to the roleplaying experience. After all, what is roleplay if you don’t communicate with your fellow players?

There isn’t much to say about conversation that hasn’t been touched on already. “Staying in character” is when what you say is diegetically communicated in the game-narrative. “Table talk” is when you are not adopting your character, but speaking in the meta-narrative. Even the Charisma stat is in the same problematic boat as Intelligence.

Now, I could reiterate all my arguments against intelligence as a stat here, but I’m going to go in a different direction instead: specifically, how to make charisma (and by extension intelligence) more useful in-game.

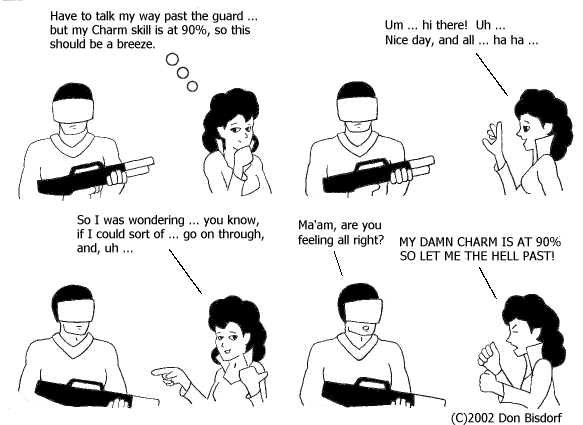

Usually, if a character wants to persuade or beguile another character, the GM either asks for the player to communicate what their character does and judges if these words are suitable to convince the NPC; or the appropriate skill is chosen from the character sheet and the dice are rolled.

But conversations aren’t just ways of flipping switches in people’s heads, just like combat isn’t just a way of moving enemies aside. A lot of games that include combat have a fairly complicated ruleset of moves; there are hit points, armor, attacks and defenses, aiming, and any number of conditions and statuses to make for an interesting and engaging strategic conflict. RPGs can conceptualize combat as complex. We understand the idea of a fight having an ebb and flow, a punch-block parry-thrust system of tug-of-war until one side gives up. We can gamify that. There’s a whole history of combat mechanics through all sorts of game genres.

Conversation is nowhere near as complex in RPGs. Why are we still neophytes with social interaction?

True, Social Combat is definitely a thing in some RPGs, and different systems have played around with it to varying degrees of success, but it’s never reached the same level of strategy the way that combat has. Even Social Combats tend to drastically simplify conflict, while most systems don’t bother and collapse conversation along with any number of other complex systems to a single roll.

Previously, I asked what would happen if we simplified complex combat mechanics into result rolls like we do with conversation. Now I’d like to ask what would happen if we complicated conversation to make it more like combat.

The obvious response is “but conversation is boring, and that’s why we use single rolls.” That’s all well and good, but it underscores the idea that its not the dice that are boring, but the act of conversation. Couldn’t we make conversation more interesting?

Because social interactions are complicated. Take it from someone who has had to actively study human interaction to be any good at it; conversations are every bit as difficult and intricate as Pathfinder’s combat system, and just as influential: Did you charm your opponent? Terrify them? Confuse them? Will they do what you ask because they think you are smart, or because they want you to like them? Did they walk away frustrated, or vengeful? Did you use the proper conversational shibboleths? Did you chose the words with the right connotations? Did your persuasiveness gain you a new enthusiastic ally, or a cautious and curious bystander? Heck, was there a misunderstanding?

And the answers to these questions can linger; if you face-plant in front of the king then word will spread. Reputations last; you might be at a disadvantage with your social dealings until you regain your social status — and if that sounds similar to being at low hit points until you get healing, well, you’re paying attention.

I’m not just asking for more rolls in a conversation to turn a result roll into a series of skill-checks. Without clear mechanics, the dice could turn an otherwise acceptable dialogue into a farce. A whole series of good rolls could be wiped away by a single bad roll. Players may feel the need to throw out lies, pleas, flattery, and threats like the worst kind of ping-ponging LA Noire scene. NPCs swing back and forth in kind, going from calm to irate to delighted and back again as the dice play merry havoc with their psyches.

Now, am I asking for battle-grids and moving miniatures about a board with social attacks, emotional defenses, and mental-health points?

Why not? I promise you, the most detailed combat strategy is nothing compared to the tactics of savoir faire: who you stand next to, where you position your fan, what kind of silent communication you take part in, all the way down to what you are wearing. Every ball could be a battlefield where a swift sweep across the floor and clever use of a lace handkerchief could be just as gripping as a barbarian hurtling an axe as they vault over an ogre’s corpse.

And don’t think it isn’t possible to put combat complexity into other aspects of a game. Someone is wounded and bleeding out? Roll for each action in your attempt to stabilize them. Do you tie the gauze too tight? Do you mix the poultice wrong? Did you inadvertently give them an infection? What if you viewed each wound as a separate monster? What if every disease had a stat-block?

We could do the same thing with any complex system. Minigames abound in RPGs, and any significant moment in the story could certainly be deserving of a significant minigame to go along with it.

But not every conversation is a summer dance or masquerade ball. Some conversations are smaller, quieter, and not suited to extensive strategic mechanics, much how not every combat requires a battle-map. Handling price haggling with multiple persuade and deceive rolls can become dull very quickly. If there is a solution in making conversation more interesting, perhaps it resides not in making the dice more complex, but the situation itself more detailed.

Perhaps convincing a king requires convincing his advisors. Perhaps that means a battle of philosophical wit with the seer, a drinking contest with the general, a moral or theological debate with the priest, a bit of a haggle with the treasurer, and a promise of future favor to the princess. Maybe a repair-man doesn’t care about fancy words, but a mechanics roll would show you know your stuff. Maybe conversation doesn’t have to be just another key in the key-ring for getting past this guard or spending just a few less coin.

Now, all of this is far more mechanically focused than some might be comfortable with. There are those who prefer the GM simply dictating whether a player’s offer “works” or not; but others find that too subjective, too much like they’re being asked to impress the GM instead of actually engaging with the fiction.

And even if a player is mechanically inclined, if they prefer result-rolls they might chafe at the firm grip action roles have on the narrative. “What do you mean I have to roll again?” they might say. “I already persuaded the King with my first persuade roll. Now I have to roll again just because you say so? Because I didn’t explain the complex details of my plan in the first breath? Are you just going to have me roll until I fail?”

There must be some middle ground, yes? Between the multitude of action rolls and the single result rolls, there must be some way of creating engaging and dramatic scenes of conversation, chase scenes, crafting, and research, mustn’t there?

Perhaps! Next time, we’ll look at Clocks.