Of Grub and Grain, and Skipping the Boring Bits

Of Grub and Grain is an RPG supplement — a minigame, if you will — about cooking. Cooking is an often overlooked aspect of RPGs, generally falling into the same pit of uninteresting chores that we would simply rather not take part in. Generally, Cooking is dealt with the same way that eating is; ignoring it completely.

You ever notice how characters in RPGs never go to the bathroom? They never really “get hungry,” either. Oh, they eat of course, but only whenever there’s a plot-important reason to do so. If a player suddenly decides its lunchtime and goes to the local tavern, you better believe a quest-hook is going to be drinking in the corner.

It’s the same thing with romance. If the story doesn’t directly involve romance, it’s like it doesn’t exist. We can skip long travels across the ocean, reading books, fixing holes in clothing, cleaning a house, or any other kind of non-adventure “chore” that is vital in our lives, but never the sort of thing people write epic poems about.

This is a common trope in our stories. The simple fact is, anything included in a story has to be important, so we have to remove everything that isn’t.

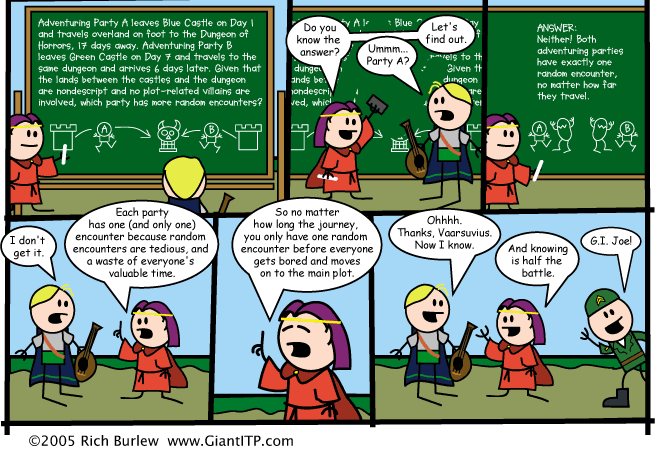

So we include tense conversations and climactic battles while ignoring regular meals and getting ready for bed, but adventures have chores too; little things that have to be done but aren’t exactly exciting. Walls have to be climbed over, rickety bridges crossed, rigging hoisted, books researched, and supplies bartered for; all things that actively affect the story, but aren’t exactly gripping.

We could spend an inordinate length of time adjudicating rules and crafting bespoke minigames, trying to make these chores “fun,” or we could just handle them all with a quick die roll. An evening spent gossiping at the pub? Roll to see how much you learn. Need to build a car? Give us a roll to see if it sticks together. Cooking a meal for the party? Roll and see how tasty it is. On the road to the next town? Roll survival, and that will comprise everything from finding berries to setting up tents and fending off wildlife. Researching a powerful spell? Roll and see how long it took. That long? Good thing we didn’t roleplay it all!

This act — a quick roll that skips over something long-term — I will call “result rolling,” because we only care about the results. We don’t care what you actually did to pick the lock, we just want to know if it worked. You can say you used a butternut glaze on the roast, that’s fine, but what matters is if your guests liked it.

It’s easy to assume, based on these examples, that result rolling is exclusively a means of “skipping over the boring bits,” and while that is one use of result rolling, it is not the only use.

See, result rolling, while great for “getting to the good stuff,” can also be used to narratively liberate the players. It gives players a clearer sense of control; if they only have to worry about a single roll, players are free to skip over when or how they want to use an asset, and just focus on if they do.

At the same time, result rolling is perhaps more susceptible to good or bad luck. Rolling for each separate action in a complex scene allows for players to have more engaged control over a character and their behavior. Each move is a counter to the last, and a single failed roll can be mitigated with clever strategy. It smooths out the bell-curve so a single unlucky roll doesn’t ruin what might be a very important moment.

Perhaps the most interesting use of result rolling that I’ve seen is in combat: if a system doesn’t have rules for backflips, sword-flourishes, or bad-ass moves in combat, then handling the entire combat in a single roll can allow for more interesting or dramatic scenes.

Some of you just felt your stomachs churn. A thousand problems just flew through your mind: “how do you handle asset expenditure?” “There are so many different flavors between success and failure.” “Doesn’t this make a complex and interesting system like combat boring?” “Sure, for a random encounter, maybe, but not for important battles.” “What, you just say they won the fight and move on?”

Well…yes. Isn’t that what we do with persuasion rolls to get past surly bouncers? Just say “you convince them” and move on?

Okay, not really. Usually there’s a bit of narrative structure around it. “Oh, alright, but I’m watching you,” says the bouncer, stepping aside and opening the gate.

Why can’t we do the same for combat? With a good roll, you squish the spiders, toss the zombies over a cliff, and keep walking.

Most RPGs encourage the players to embellish descriptions of their actions. Instead of just attacking, you “swing your sword over your head while bellowing a battle cry that chills the hearts of your enemies.” You’re not just “grappling,” but wrapping your arms around the beast’s neck as you spin onto its back with reckless laughter. You’re shooting enemy drones out of the skies with pinpoint accuracy while rolling out of the path of oncoming hoverbikes. You’re telling a story.

But not every system is comfortable with that kind of narrative. Riding the back of a dire-alligator through your enemies ranks is a brilliant action-scene…until you get shoved off on your second turn by a lowly pike-soldier. That awesome moment lost forever thanks to an unlucky roll on your part.

What if, instead, you knew you were going to win the fight? Then you’re free to describe the entire action scene, complete with highs and lows as you see fit. Maybe the GM charges you to suffer some kind of defeat in the conflict, but gives you free reign to dictate the dialogue as your nemesis shoves their blade into your side, only to be shoved back by your determined kick. You are free to dictate how the battle ends with you astride your crocodillian mount, waving a bloodied saber in one hand and your tattered standard in the other, laughing as your nemesis flees before you, even with blood pouring down your side.

It allows you to “play the end,” which is a topic we will broach next time.