Runecairn, and Video Game Influence

Based on Cairn and Into the Odd, Runecairn is draped in Norse and Viking mythology, and inspired heavily by Dark Souls and Bloodborne games. There are re-skinned estus flasks, immortality, near continuous combat, even rules about bonfires. For all else that it does, Runecairn wears its inspirations on its sleeve.

That the game is obviously inspired at least in part by video games is not uncommon. Table-top RPGs have always had major influence on video game RPGs; consider the deluge of D&D RPG video games like Pool of Radiance, Eye of the Beholder, Dark Sun, Ravenloft, Menzoberanzan, and Balder’s Gate — and that’s just a fraction of one license. Fallout was inspired by GURPS. Vampire: The Masquerade has had multiple video game titles. Even non-licensed game series like Magic Candle, Ultima, Wizardry, and Might and Magic all owe more to tabletop RPGs than any of their video game kin.

It’s only natural that the ecosystem flows both ways.

So we have Bloodstone, inspired by Bloodborne. We have Our Stormy Present, inspired by Skies of Arcadia. We have Fight Item Run, inspired by every console RPG you can think of. Beneath a Cursed Moon is inspired in part by Castlevania, Gubat Banwa by Final Fantasy Tactics, and T-DEF is based on X-Com. Inspirations come from many places and the RPG iceberg runs deep. While Runecairn may have taken several mechanics and tone from Dark Souls in specific, the borrowed video game mechanic that interests me the most is that it is, functionally, a single-player game.

Yes, technically there are two people sitting at the table, but one is the GM who takes on the immutable role of arbiter. It’s the same relationship you have with Nintendo, Activision-Blizzard, or From Software…though hopefully with less overt abuse on your GM’s part.

You can see the influence of video game logic in a lot of different systems. Strategic combat games like 4th edition D&D or Unity have codified movement and targeting rules that could easily be turned into a video game. The amorphous and organic question of “what do you do next?” is replaced with the more codified “how do you spend your three action points?” Instead of “casting a spell,” Valiant Quest has a reagent list with elemental aspects that must be spent, complete with gold costs, akin to the old Ultima system. Crafting mechanics are prevalent in games nowadays, as are codified “conditions” which provide specific limitations.

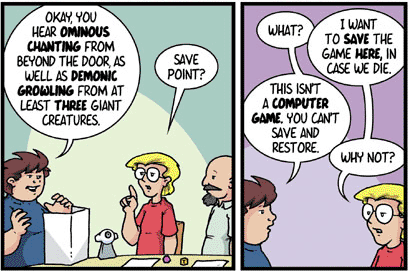

Figure 1: Trust me, we’ll get to realism soon enough.

In fact, you could make the case that while RPGs have rules, video games have laws. The more rigid a system is made, the more rules and edge-cases are codified, the more “video-game-like” the RPG is.

You couldn’t make a video game of Cairn, there aren’t enough rules. Narrative games like FATE may have more, but the inclusion of judgment-call situations, like with Aspects or stunts, make it an impossible system to code. You would have to reduce the infinite flexibility of language down to the simplified complexity of dice, something that rules-heavy combat RPGs like Lancer and Shattered have already done.

Now, is the video-gamification of RPGs a bad thing? I am a firm believer that certain stories are best served in appropriate mediums, and so why not leave the rule-heavy systems to the number-crunching machines, and turn to the “purer” (bleh) RPG experience: making it all up as you go along?

Someone could probably make the case, but I’m not interested in doing so. After all, Monopoly and Candyland are also system-first games, and therefore well-suited to video game status…but that’s not the point, is it? Never mind the fact that not everyone has a games-console in their living room, but leaving rule-heavy games to the computers is like leaving paintings to the cameras. It’s missing the point, to say the least.

Now, to be fair, early RPGs never mandated a party of two or more players. The Challenge series of AD&D books, for example, were a collection of adventures designed for a GM and one other player.

But something different happens when an entire system is built expecting this dynamic.

Like Dead Friend, for example, a game for two players where one plays a necromancer summoning the other player, the ghost of the titular friend. Shaped like a ritual, the game develops as the players create the two personas’ backstory, relationship, motives, and the tragedy that befell them.

How about Star Crossed, a game about two unrequited lovers that uses the same mechanics as Dread, exchanging the suspenseful terror of the horror genre with the suspenseful terror of the bedroom?

Or how about Wickies, where the two players are lighthouse attendants struggling to keep their cool amid the terrible torments that plague people together in isolation. Will you keep your grip on what is real, or will you both surrender to your madness?

Or there’s When You Meet Your Doppelganger on the Road, You Must Make Out With Them, which is all about…well, meeting your doppelganger and you know the title sums it up pretty well.

Playing with a group of players can be an exhausting experience. Players have to not only engage with the system and their own character, but the other players as well. Being aware of both your own responsibilities as well as your responsibilities to the game as a whole takes energy. You have to make sure that everyone gets a say in the story, appropriate attention in the action, and that the team is kept together.

If you’re playing alone, on the other hand, you can focus on your own character. You can craft your own story, and devote your energies on overcoming the obstacles that the GM throws your way. You don’t have to negotiate with your fellow players about who gets what items, worry about another player screwing up your plans, or share the camera’s focus if they need to have their own character-developing story beat.

Dual RPGs are fundamentally intimate affairs, or at least more intimate than the standard multi-player RPGs. The other player has no other recourse but to react to you. Not the world, not another player, but you, specifically. Every word you say is not to the table as a whole, every action is not a part of a wider tale and established world, but a specific and singular offering to another person to react to as they see fit.

There is a palpable difference between conversing with a group and conversing with a single person. There is a strange intimacy that makes talking about sports or the weather with one person far more personal than sharing fears, loves, or hopes with a group.

You can’t step back in a Dual RPG. You can’t let another player have the spotlight, letting them craft the action with minimal input. The other player can’t look away from you; they can’t talk with a different person for a bit, you are the only other player in the game; you have to stay engaged.

Without the ability to take a breath or a step back, Dual RPGs can be intense. If a large RPG game is like a party, a dual RPG is like a date.

You may have noticed by now that I try to not separate participants in RPGs into the usual GM and Player camps. I personally think the collective-noun “Players,” as a group, includes the GM. Dual RPGs are a perfect example as to why; the GM must engage with both the system and the other players, as any player must. To say the GM is not a player is to set them in the same cubbyhole as video game code.

Dual RPGs are perhaps a poor example of a single-player RPG, then. Part of the point of single-player is that we can’t always find someone to play with, whether because of homework, the late hour, distance, or the weather.

So what would a single-player game really look like?

Next time, we’ll talk about Solo RPGs.