Lancer, and Why We Play

Lancer is, to quote the book: “a mix of gritty, mud-and-lasers military science fiction and mythic science fantasy, where conscript pilots mix ranks with flying aces, mercenary guns-for-hire brawl with secretive corpo-state agents, and relativistic paladins cross thermal lances with causality-breaking, unknowable beings…players adopt the roles of mechanized chassis pilots — mech pilots — comrades together in a galaxy of danger and hope.”

The system itself is quite rich. With a defensible claim to the most strategically balanced RPG currently available, Lancer is a system that requires careful consideration of forethought, resource management, teamwork, and luck. There are ranges, area-of-attacks, damage types, conditions, statuses, hit points, stress points, structure points, core powers, and more. By managing to make all the complex economies interact and play off each other in a dizzying array of complexity, Lancer manages to make each combat a puzzle.

But only inside the mech.

See, your Lancer pilot doesn’t live in a mech, they just work in one. Outside the mech they have to deal with merchants, officers, superiors, subordinates, politics, and the day-to-day minutiae of living on the outer rim. Outside, there is no need for “system points” or “hull checks.” Outside the mech, if your pilot wants to do something, you just roll a twenty-sided die. If you roll an 11 or over, then your character succeeds. If your pilot happens to have a selected a “skill-trigger” that applies to the situation then you get a +2 bonus for the action. Simple, elegant, and entirely narrative focused.

If these two descriptions sound like you’re playing a simplified version of FATE outside the mech, and an improved version of 4th edition D&D inside the mech, then you’d be spot on. That’s exactly what it’s like.

Lancer as an RPG has an incredibly firm dividing line between story and system. Inside your mech is almost exclusively tactical. There is narrative and roleplay, yes, but only as much as you can squeeze in through the cracks. Outside the mech is entirely narratively focused. There are rules, yes, but they are focused on shared narrative instead of stats and die-rolls.

This leads to an important question about Lancer…is it a brilliant mix of narrative- and strategy-based play? Or is it unfocused?

Playing a narrative-focused system requires a very different kind of skill than the more game-focused ones. After all, the point of a game is to win, right? I’m supposed to kill the dragon, or win the race, or swipe the jewel — I’m supposed to try to succeed.

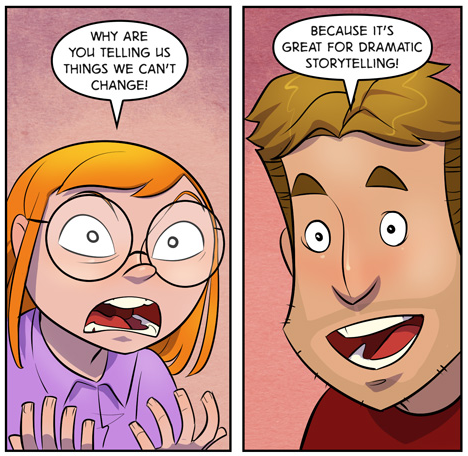

But narrative gets in the way of that. If the “correct move” is to kill the cultist before they summon the demon, what does that say about the paladin who tries to redeem them instead of striking the killing blow? The goal of RPGs isn’t just to win, but also to tell a good story. When one gets in the way of the other, different people will fall on different sides of the divide.

Figure 1: Some people want agency, others want an audience.

Some people like storytelling, others like playing with systems. Obviously there are people who like both, but do they like them so separate? Do the players who love strategy wargaming want to have to step outside their mech to deal with narrative play half the time? Will storytellers tolerate so much strategic combat barging into the middle of their stories?

Or is this separation actually more focused, as the strategic wargaming is not muddied by narrative and the narrative remains untarnished by strategic puzzles?

For the record, I love Lancer; but it brings us to the important question: Why do we play RPGs?

Because we enjoy them, obviously, but why? Different reasons for everyone, and ultimately entirely subjective ones. Some people love a challenge, others love drama, and some just like being included.

Now, I’m no sociologist, and I’m not about to start categorizing “types of players.” Instead, I’d like to look at a few things that RPGs provide to players. If we’re so inclined, then, we could come up with some theories about “why people play RPGs.”

Community

This is the obvious one. Most RPGs involve large groups of people, anywhere from four to seven on average. RPGs are like most other “game night” activities in that they provide an excuse to gather together in a social situation.

I wonder if this is where the idea of the “casual player” comes from? I can imagine there are players who join in more for the camaraderie than any distinct passion for RPGs. They might be perfectly happy playing D&D, Pandemic, Monopoly, or even just sitting and talking. They wouldn’t care about “being good at the game,” they care if they enjoyed their time playing it.

A Challenge

Especially with combat-heavy RPGs or groups with combative GMs, this is perhaps the most “board game” aspect of RPGs. Players are asked to stretch their strategic muscles to solve puzzles.

I’m using the term “puzzle” broadly here to mean any kind of mental exercise, from strategic combat to creative solutions. This is perhaps the most “antagonistic” side of RPGs; not necessarily with fellow players but rather obstacles to progress that require “solving.” They could be solved with a sword, a compromise, or a creative application of flour and water.

The solutions could involve a solid knowledge of the system’s rules and loopholes, or lateral thinking within the narrative. Either way, it’s easy to see how players might come to RPGs to feel a sense of accomplishment after overcoming a difficult challenge.

An Experience

This is the other side of the Story/Game spectrum. We humans love stories, and a dramatic tale of heroes, monsters, the earth in peril, or a lover scorned is sure to draw a good number of us. As an added bonus, RPGs allow us to take part in these stories as participants, rather than as observers.

The fact is, this world can be quite dull. We can’t personally solve international plots, slay monsters, or make first contact with an alien species. Yet those are the stories we are told, so we find ourselves with a disconnect; one we resolve through roleplay.

This is perhaps the more collaborative side of RPGs, with players encouraged to make decisions that are interesting or dramatic over ones that are perhaps more efficient, pragmatic, or “correct.”

A Mask

The truth is, I can never be anyone but myself, but who myself is…well that can change. I could be kinder, meaner, more assertive, more polished, a different species, a different gender, a different being altogether. I could be different.

It can be hard to decide to change, still harder to make the change. It requires a quality I can hardly call strength, nor bravery…it takes a beautiful madness to see the life you live and say that your own constructed imagination — free from the influences of the outside world — can show you a better way to live.

I understand the urge. RPGs allow us to be different in a way that might terrify us in real life. They give us the chance to express ourselves with the cover of play and performance. We can rage, cry, or behave in any way we wish to, all in the safety of the game.

Agency

One of the major causes of stress in our lives is the feeling of “loss of control.” When someone else has control over our lives, laws, jobs, etc., it can be stressful; like we’re on a roller-coaster, getting yanked about on a chain, forced into situations we don’t want to be in.

RPGs, on the other hand, are shaped by the actions of the players. By erring on the organic and adaptive side of play, RPGs can provide the thrill of creation and purpose. Players are encouraged not just to solve problems, but to take part in the act of creation. Rather than passive observers or obedient rule-followers, players are agents of change.

You cannot play an RPG that is not, ultimately, your own.

Now, just to clarify: none of these provisions are morally better or more “pure” than the other. You aren’t a better or worse person for wanting to play RPGs for this reason instead of that one.

And don’t go thinking this is an exhaustive list! You may be able to think of other things that RPGs bring to the table that other kinds of games don’t. These are just the ones I thought of.

I’ve listed these as a framework to build on; a method of exploring “what RPG players want.” As you continue your expedition through the jungles of RPG-land, I only ask you keep some of these provisions in mind. I was surprised at how often they become relevant.

One final thing I want to suggest: success in RPGs are fundamentally dependent on our fellow players. If we incorrectly assume we’re all playing for the same reasons, we may make the mistake of blaming failed games on people who “weren’t playing right,” when really the problem was “we were playing different games all along.”